There were 50,000 American servicemen who were posted in New Zealand during World War II, an event that would have a lasting impact on local culture.

Among the Marines who arrived in June of 1942 was Norman T. Hatch, head of a cinematography unit, who in his 11 months in New Zealand shot at least 29 reels of film intended for newsreels and hundreds of photographs of Marines in training and at leisure.

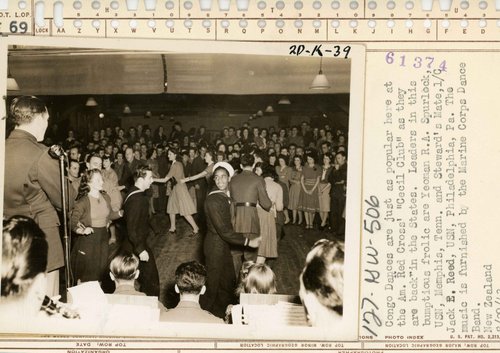

He and the photographers under his command had exclusive access to now-vanished sites of great historical interest, including sprawling Marine campgrounds and the Cecil Club, a café and jazz lounge operated by the American Red Cross for homesick troops in Wellington central. They also captured Americans, from ordinary soldiers to First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, meeting New Zealanders in their homes, workplaces and marae.

After returning to the United States, Hatch’s footage of the Battle of Tarawa won an Academy Award, but his unique views of New Zealand were never used to make the intended newsreel. Nor were they shown in New Zealand; the arrangement between New Zealand and United States heads of state meant that reporting or recording of any of the Marine Corps’ movements were banned. Very few people got to see or even knew about the collection after the war.

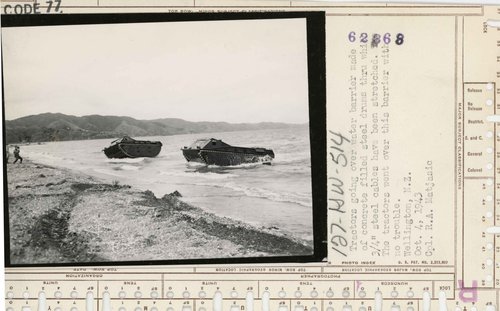

Original photo caption:

Tractors going over water barrier made of concrete filled steel drums thru which ¾” steel cables have been stretched. The tractors went over this barrier with no trouble. Credit: Cpl. R.J. Matjasic (Wellington, 04 October 1943).

Decades later, a chance meeting between Hatch and New Zealand filmmaker Steve La Hood set in motion a digital repatriation of Hatch’s material. La Hood was in Quantico, Virginia to accept an award for a 2007 film he made about the Marines and people who remembered them, A Friend in Need, which became part of a longstanding exhibition at Old St Pauls. Steve described their encounter at the National Museum of the Marine Corps in a recent interview with Ngā Taonga:

"I got sat at a table with this old geezer and a couple of others. And it turned out that the old geezer was Norman Hatch. He was 91 and he was a cranky old guy. The first thing he said, when I sat down, he said, ‘Yeah, saw your film.’ Okay. ‘See you used all the National Film Unit stuff, but you didn’t use any of my shots.’ I said ‘Your shots?’ and he said, ‘Yeah, I was there. I was there for 11 months in New Zealand, with a Marine Cinematography Unit’, and I went ‘…a Marine Cinematography Unit?’

Then the woman sitting next to him, Susan Strange, who was his aide-de-camp and a researcher, said, ‘Norm’s got a whole lot of stuff here in the archives’. I said, ‘Well, what does it look like? I mean, what kind of film did you take?’ And he said straightaway that the New Zealand film crews weren’t allowed into the camps. So they weren’t allowed to see what was going on. And he was in the camps filming what was going on. I said, ‘God I’d love to see that footage’. And then he said, ‘Well, I don’t know where it is, Susan might know.’

A couple of years later, he was gone. Norm died in 2017. He was 96, when he died. And that year is when Susan said ‘I’ve found a lot of footage, a lot of it is on U-Matic. You don’t want to see that. So what I’m going to try and do is locate the original negative source. And if you can raise the money, we’ll get them re-transferred’.

Of course, we get stuck into that process. We get a lot of it done. And then she finds all the photographs that go with it. And I’m going wow, this is amazing. This is an extraordinary tranche of footage of New Zealand as seen by Americans."

La Hood and the Kapiti United States Marine Trust (KUSMT), with a grant from the US Embassy in Wellington, were able to get a significant amount of the films and photographs digitised and returned to New Zealand (although, in examining the collection, La Hood found intriguing hints that there may be still more over there). Regrettably, most of the footage is silent; the audio tracks that would have accompanied the completed newsreel could not be located at Quantico. They then deposited the collection with Nga Taonga Sound & Vision.

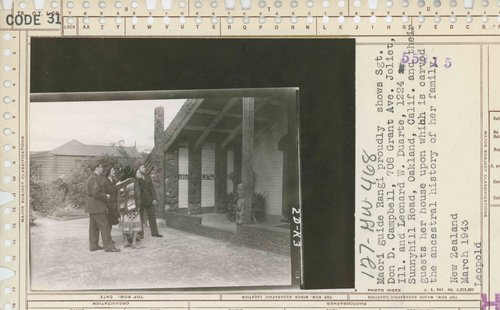

Original photo caption:

Maori guide Rangi proudly shows Sgt. Don D. Campbell, 708 Grant Ave. Joliet, Ill. and Leonard W. Duarte, 1224 Sunnyhill Road, Oakland, Calif. and their guests her house upon which is carved the ancestral history of her family. Credit: Leopold (March 1943)

Mindful of the approaching 80th anniversary, and KUSMT’s plan to open an interpretation centre at Camp Paekakariki on June 14, our archivists raced to catalogue the newly acquired items, and a small team undertook the work of researching, interpreting and getting the collection online. A Mātauranga Māori Outreach Specialist began studying the films and photographs, identifying as many of the Māori people depicted as he could, and contacting their descendants to ask for kaitiaki permission to upload their likenesses. We’ll share more about that process in a future blog.

So what makes the Norm Hatch collection significant? Archivist Shane Farrow describes his first encounter with it:

"Steve had some of this footage on his laptop and proceeded to reveal astounding footage of Marines landing on Paekākāriki Beach in the early dawn, with warships in the background, US Airforce planes flying overhead and tanks mounting the sand hills. It was a full-scale landing operation as well as a training exercise rolled into one, with a bunch of camouflaged Marines waiting in the sand hills. Howitzers were firing shells and land mines were being detonated in this simulated tactical war scene!"

The films and photos reveal a view of Wellington and Kapiti that most of us have never seen. The arrival of the Marines abruptly changed the whole look of the area – it was hard for anyone to miss them. Large camps were constructed on the Kapiti Coast, namely Camp Paekakariki, Camp Russell and Camp McKay. Smaller camps went up at Pāuatahanui, Judgeford Valley and Titahi Bay. Businesses sprang up in the city, some run by the military, to provide the new arrivals with services like dry cleaning and American-style foods, which locals also learned to enjoy. Marines trained for combat on beaches and in the bush, and recovered from injuries received in the Pacific at hospitals staffed by local and American nurses.

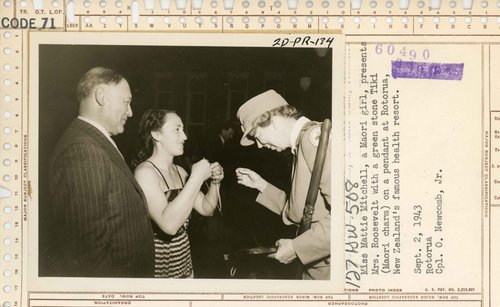

Original photo caption:

Miss Mattie Mitchell, a Māori girl, presents Mrs Roosevelt with a green stone Tiki (Māori charm) on a pendant at Rotorua, New Zealand’s famous health resort. Credit: Cpl. O. Newcomb, Jr (Rotorua, 02 September 1943).

When they were off duty, Marines missing the comforts of home life were paired with local families and joined them for meals and weekend home stays. Parties travelled to locations including Rotorua for encounters with Māori culture and history; among the famous faces that appear are Sir Apirana Ngata and Rangitīara ‘Guide Rangi’ Dennan. In August-September 1943 First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt toured New Zealand and met soldiers and local war workers. Hatch and his team captured all of this.

Where New Zealand journalists were not permitted to go, the Marines cinematographers and photographers were there. Information was strictly controlled by both governments – news that reflected badly on troops or might harm morale was censored – and security was of course tight around the camps. One of the things that is so interesting about the Norm Hatch collection is that it shows normal people and familiar places, but through the specific lens of Americans with a public relations mission, undertaken as part of the war effort. That shouldn’t be taken to mean that the images are somehow fake or unreliable; just that there’s a lot deliberately (and necessarily) left out of frame.

In truth, the relationship between locals and the Americans was sometimes uneasy. Some residents opposed the war in general, or the presence of American troops in particular. Some white servicemen, accustomed to segregation at home and in the military, made themselves unwelcome by objecting to the presence of Māori in public spaces. On 3 April 1943, Americans attempted to deny service to Māori at a bar, leading to a riot between Marines and civilians that was nicknamed ‘the Battle of Manners Street’.

Sexual jealousy was also an issue, leading some New Zealand men to bitterly nickname their rivals “bedroom commandos”. Many young women found the Americans far more glamorous than the local men they were used to, and well-paid, well-dressed young visitors had no trouble finding dates. About 1,500 women married Marines during their short stay, including LaHood’s aunt, who left with her new husband and never came back. He explained:

"One of the things that women always said about the Americans was ‘I can’t believe how white their teeth are’. They were like super humans, they were on average, six inches to 12 inches taller than anyone else. And then because of their education system the men had grown up with girls at school. So they could talk to women, in a way that clunky New Zealand monosyllabic blokes simply couldn’t do. They were generous, and they were smiley and fabulous and young and vaguely innocent, and the girls just fell for them, like you wouldn’t believe."

Original photo caption:

Credit: Cpl. McClure (Manurewa, 21 July 1943).

In fact, a lot of New Zealand civilians had their expectations permanently shifted by encounters with the Marines. Life in the early 40s was very different from what it is now, and both sides of this encounter found the other exotic and sometimes baffling. You can see this in the captions attached to the still photographs, typed out on index cards by the Marines. In just a sentence or two, they convey not only locations, names and dates, but cultural information and analogies for the folks at home. Rotorua is described as a “famous health spa“. Saveloys are “New Zealand’s equivalent to America’s hot dog“.

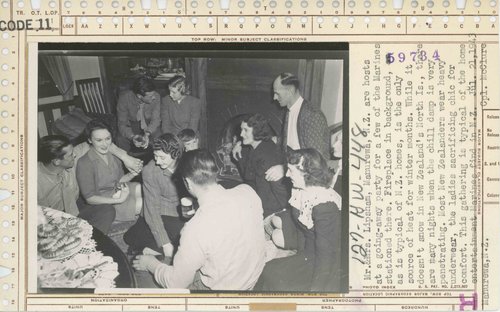

A photo of a gathering at a home in Manurewa (S319594) is captioned:

Mr. & Mrs. Lipsham, Manurewa, N,Z, are hosts at a going-away party for a few of the Marines stationed there. Fireplace in background, as is typical of NZ homes, is the only source of heat for winter months. While it doesn’t snow in New Zealand’s North Is., there are many nights when the chill damp is very penetrating. Most New Zealanders wear heavy underwear, the ladies sacrificing chic for comfort. The gathering is typical of the home entertainment Marines find in NZ.

The Norm Hatch Collection takes viewers back to a moment when relatively isolated New Zealanders, in the middle of a stressful and materially depriving war, found themselves intimately involved with a superpower on the rise. As Steve LaHood described it to us:

"This is an extraordinary period in New Zealand, really. It’s only 18 months long. But it’s the point at which I believe New Zealand stopped being a lonely outpost of Britain in the South Pacific and started seeing the future as an American future."

Hero image: Congo Dances are just as popular here at the Am. Red Cross “Cecil Club” as they are back in the States. Leaders in this bumptious frolic are Yeoman R.A. Spurlock, USN, Memphis, Tenn. and Steward’s Mate, 1/C Jack E. Reed, USN, Philadelphia, Pa. The music is furnished by the Marine Corps Dance Band. Credit: S/ Sgt. R.E. Olund. (Wellington, 29 August 1943)