By Sarah Johnston

This blog comes from Sarah's blog - World War Voices.

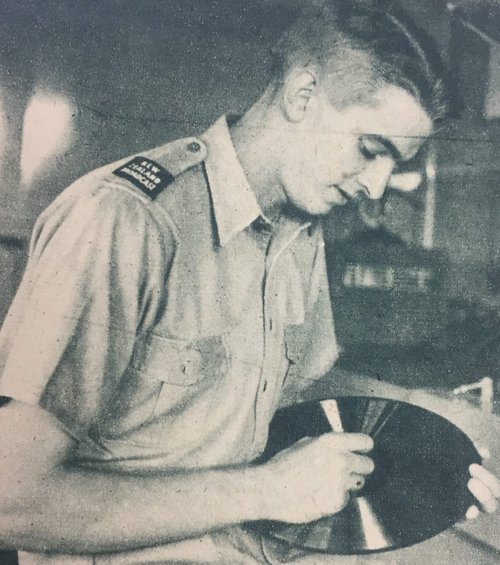

The recordings were made on the converted Canadian passenger liner, Empress of Japan. These discs were sent back to New Zealand from the various ports of call they stopped at enroute. The surviving recordings, plus correspondence from the men themselves, convey a sense of anticipation that many members of the New Zealand Expeditionary Force must have felt; the trepidation of heading off to war tempered by the chance (for most) to travel overseas for the first time.

The Broadcasting Unit sailed from Wellington on 27 August 1940. Three days out from New Zealand, their troopship convoy of the Empress of Japan, Mauretania and Orcades, paused in the Tasman Sea to farewell their escort, the cruiser HMS Achilles, which was heading back to New Zealand. The convoy was joined by an Australian contingent sailing out of Sydney, and HMAS Perth and HMAS Canberra would take over escort duties for the next leg of their journey.1

The Achilles was already the toast of New Zealand in 1940, after taking part in the Battle of the River Plate in the South Atlantic in December 1939, where it had become the first New Zealand unit to strike at the enemy, firing on the German pocket battleship Graf Spee. The German crew subsequently scuttled their damaged vessel, and the battle was seen as a victory and great morale boost to Britain and the Empire.2

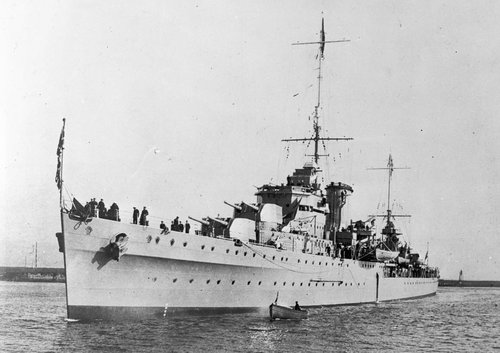

On their return to New Zealand in February 1940, Achilles and her crew were given a hero’s welcome, with parades and receptions in Auckland and Wellington. In this silent film footage taken by Lt. Richard Washbourn (who would earn a DSO, CB, OBE, and eventually become a Rear Admiral and Commander of the Royal New Zealand Navy), you can watch her crew in the South Atlantic. There is no footage of the battle (understandably) but the unscripted, home movie gives a great feel for life on-board and leave onshore. At the end of the online footage, as the cruiser enters Auckland on 23 February 1940, we see huge banners ‘Well done Achilles’ and ‘Bravo Achilles’, adorning harbour-front buildings, as well as hundreds of waving Aucklanders crowding the docks and small craft which sailed out to greet her.

‘HMS Achilles’ with some of the crew on deck. [Alexander Turnbull Library]

Therefore, it would have been quite a fillip for the men of the Third Echelon to have this famous New Zealand vessel as their escort out of Wellington, later that same year. So much so, that when Achilles prepared to hand them over to an Australian escort and turn for home, the Broadcasting Unit ran out their microphone and recorded the event on deck on 30 August 1940.

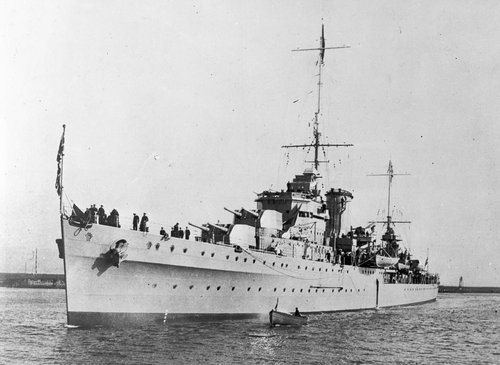

Mobile Unit commentator Doug Laurenson (who is seen in the Listener magazine cover photo at the top of this blog) narrates the recording, which was recorded in four parts over two lacquer discs which have been digitised and made available to listen to on Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision’s website. In the first, he explains Achilles is to cruise around all the ships of the convoy and farewell them each in turn. Men are lining the decks and clustered around portholes. It is 5pm and the Tasman Sea is ‘beautifully calm’ as the sun sets.

In the second, he observes on the decks of their sister ship (Mauretania) the scarlet capes of New Zealand army nursing sisters, dotted among the soldiers and crew. Laurenson describes Achilles as it pulls alongside, flying a string of signal flags, which are being interpreted by his ship’s signalmen. In an aside, the kind of minor detail which enriches so many of the Mobile Unit recordings, he notes the men on his vessel ‘have had their vaccine inoculations today and are all nursing rather sore arms, so they will be sure to wave to Achilles with the other arm’.

Finally, in the third part of the series, Achilles’ crew is heard giving three cheers to the men on the Empress of Japan, and receive the same in return. Through the noise of the wind on the open Tasman, Achilles’ band can be heard playing on deck as her ratings sing ‘the Māori song of farewell’ (“Pō Atarau/Now is the Hour”) for the Third Echelon’s men. They return the compliment by singing “For They are Jolly Good Fellows” as Achilles slips astern and heads for home, severing one final link with New Zealand.

Nearly a week later, the first stop for the 2 N.Z.E.F. convoy was Fremantle, the port for Perth in Western Australia. Here the Mobile Unit reported that the Kiwis were given a grand welcome by the locals, with cheering crowds and cars meeting the ships, ready to whisk men off to see the sights, as most had 12 hours’ shore-leave.

The unit’s assistant engineer, 23-year-old Norman ‘Johnny’ Johnston, wrote to his parents about visiting Australia: ‘The train journey from the port to the city was a great experience – people all along the way cheering and motor cars tooting their horns. Our first job was to post what records we had made back to N.Z…They were 12 pounds weight of discs and as the rate is 5 pence per half ounce and we had to send them collect, it will be a pleasant surprise for the firm [the NZBS.]’ Johnston also called on the Australian Broadcasting Commission’s local radio station and was given a tour of their facilities, and then visited an aunt of his mother’s who lived in Perth, before catching up with other NZEF men in town for an obligatory beer and dinner at a city restaurant.

New Zealand Broadcasting Unit assistant engineer Norman ‘Johnny’ Johnston, labelling a lacquer disc [Photograph from ‘Cairo Calling’ – Egyptian State Broadcasting Service magazine, 30 November 1940. Archives NZ ADQZ 18886 WAII1 R20107884]

‘The New Zealanders took complete control of the city and there were some of the funniest sights I’ve ever seen. Two Auckland chaps pinched horses from somewhere and galloped up and down the main street. Others stood at crossings controlling traffic. The local inhabitants were fortunately very long-suffering and didn’t seem to mind a bit’.3

Back on board, the commentator Doug Laurenson made a six-part series of recordings about impressions of their first shore leave and the waving crowds that greeted the New Zealanders. (Note that due to wartime censorship neither Fremantle, Perth nor Australia are mentioned by name in his report.) Special troop trains carried the men from the port into the city throughout the day, with both sides of the track lined by cheering locals. ‘We were welcomed by thousands of waving hands: children lined up at the windows of their classrooms… people grouped in their gardens and back verandahs, on overhead bridges and shop doorways…all stopped to give us a cheer and the universal sign ‘Thumbs up New Zealand!’4

In parts two and three of this series, which is entitled ‘News from the Troops’, they recorded the unit’s first greetings from New Zealanders for broadcast to families at home. It seems the unit was still establishing a format for this type of broadcast, and frustratingly, none of the speakers are fully named in these recordings: a sergeant named ‘Basil’ sends greetings to Christchurch, Okuru and Jackson’s Bay (in South Westland), a man named ‘George’ sends greetings to Auckland, Whangārei and Kaukau, and an unidentified nursing sister says hello to ‘Mangatawiri’ (sic. – possibly Mangatāwhiri or Maungatāwhiri). She describes how the nurses on board enjoyed their first shore leave, with hospitality provided by the local Perth nurse’s association, including dinner and dancing.

Hay Street, Perth, c. 1940s [Courtesy Museum of Perth]

Happily, parts four and five are more satisfactory, for although ‘Bert’ the Quartermaster Sergeant interviewed in them is not fully named, he helpfully ends his recording by greeting ‘39 Tarikaka Street, Ngaio’ (Wellington). Using this detail and his rank, I was able to identify him on Auckland War Memorial Museum’s Online Cenotaph database as Albert John Wyeth 27368. Bert gives details of a typical day on-board a troopship, from reveille at 6:30am, through roll call, physical training, games and route marches on deck (to recorded music provided by the Broadcasting Unit). A World War I veteran, Bert says this troopship is about four times larger than the one he travelled on ‘last time’. He notes boots must be worn during route marches, in order to keep the men’s feet in shape for when they finally get back on land. Blackout is observed on deck after dusk, so no smoking is permitted outside. He says the weather has been splendid, making it a most enjoyable voyage, ‘especially for those lads, for who this is their first trip’.5

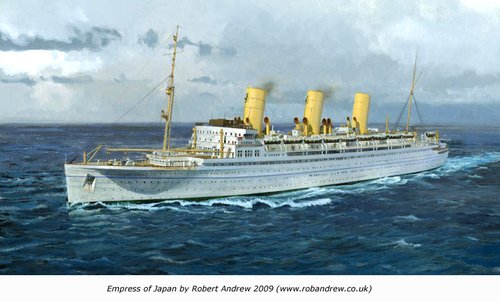

This first of what would be many thousands of recordings of messages for New Zealand radio listeners, ends with a Canadian. Captain John Wallace Thomas, master of the ship Empress of Japan, sends a few words to the friends and families of his New Zealand passengers. Before the war, his vessel was a luxury passenger liner of the Canadian-Pacific company, sailing the Vancouver–Yokohama–Kobe–Shanghai–Hong Kong route.

Empress of Japan in her pre-war livery. [Image courtesy of The Empress of Scotland: an illustrated history]

Her Canadian and Chinese crew carried celebrities such as American baseball legend Babe Ruth across the Pacific.6 Requisitioned in late 1939 for war service, she ferried New Zealand and Australian personnel to the Middle East for several years, changing her name to Empress of Scotland after Japan entered the war with the attack on Pearl Harbour in December 1941.

After safely delivering the New Zealand Third Echelon to their destination, Captain Thomas and his ship were to have an eventful war, surviving several near misses. On 9 November 1940 off Western Ireland, they suffered a German air attack. During the air raid, Captain Thomas and Ho Kan, the ship’s Chinese quartermaster, heroically staffed the wheelhouse, steering the ship to take evasive action. In the face of enemy machine gun fire, Ho Kan at the wheel calmly carried out his commander’s instructions from a lying position. Both men were later decorated, Captain Thomas with the CBE, and Ho Kan the BEM. Captain Thomas is one of 14 figures from Canada’s military history remembered with a bust at the nation’s ‘Valiants Memorial’ in Ottawa.7

Statue of John Wallace Thomas, Valiants Memorial, Ottawa, Canada. [via Wikimedia Commons]

Hero image: Doug Laurenson (right) recording a crew member onboard ‘HMS Leander’ in 1941. [The New Zealand Listener, 7 August 1941, cover]

References:

- Ward, Michael. Middle East Troopship Convoys 2NZEF 1939-1945. Auckland War Memorial Museum – Tāmaki Paenga Hira. First published: 24 September 2020. Updated: 6 October 2021.

- MacGibbon, Ian. The Battle of the River Plate: the New Zealand Story. History Group, The Ministry for Culture and Heritage.

- Johnston, Norman Balfour. Letter dated “At Sea”, 6 September 1940.

- Laurenson, Morgan Douglas. News from the Troops No. 2. Part 1 of 6. RNZ collection, Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision ID10977

- Wyeth, Albert John. News from the Troops No. 2. Part 5 of 6. RNZ collection, Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision ID10977

- Empress of Scotland: an illustrated history

- John Wallace Thomas, Wikipedia