With the Māoriland Film Festival having to drastically reduce its programme due to the Covid-19 pandemic, Ngā Taonga wanted to take a quick look at the history of Māori Cinema. As Taika Waititi said when accepting his Academy Award in February, indigenous people ‘are the original storytellers and we can make it here too’.

With an oral history tradition, Māori have always been great storytellers. It’s not surprising that they and their stories have a long history in New Zealand moving image.

Māori stories were popular topics for early non-Māori filmmakers. The antiquated idea of a ‘noble savage’ was a popular trope, as was the retelling of Māori pūrākau (legends and stories). French filmmaker Gaston Méliès and his Australian counterpart George Tarr both filmed features called Hinemoa, in 1913 and 1914 respectively. Both told the legendary romance of Hinemoa and Tutanekai on Mokoia Island, Lake Rotorua.

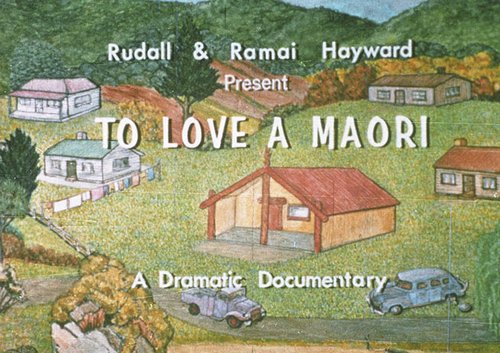

The Māori mythos was expanded by films like Rewi’s Last Stand (versions produced in both 1925 and 1940) and The Te Kooti Trail (1927 – both films were directed by Rudall Hayward). The female lead of the 1940s sound version remake of Rewi’s Last Stand was Rāmai Te Miha. When Rudall and Rāmai married, both became successful and influential filmmakers in their own right. Rewi’s Last Stand later became the first local feature to screen on New Zealand television.

Ramai and Rudall Hayward in China, S257609.

The pair made documentaries, short films and television features. Much of their work looked at Māori and other indigenous communities, including in Samoa and China. Their 1975 dramatic documentary To Love a Maori was made on ‘half a shoestring’ and looked at racial discrimination, Māori urbanisation and gender politics.

Earlier, 1952’s Broken Barrier also explored relationships between Māori and Pākehā. Produced by Pacific Films, the company were determined to accurately show New Zealand society onscreen. Their later film, 1966’s Don’t Let It Get You included onscreen performances by Kiri Te Kanawa and Howard Morrison.

The Māori renaissance of the 1970s saw an accompanying increase in film made by Māori, notably Merata Mita, Barry Barclay and Don Selwyn. Mita worked on a variety of features and documentaries, including Bastion Point: Day 507, Utu, PATU! and Mauri. Barclay worked across a number of different forms of film, television and media including Ngati, Tangata Whenua and The Neglected Miracle.

Merita Miita (Director) and Annie Collins (Editor) editing Patu, May 1983, S235855. Photo by Jocelyn Carlin.

In 1983, Merata Mita said ‘As the producer or director of a film, I’m actually in the position of the person who carried the oral tradition in olden times… it’s similar to the way whaikōrero and the stories that are told on the marae keep history alive and maintain contact with the past.’

Barry Barclay also pioneered the idea of a Fourth Cinema. University of Auckland’s Dr Stephen Turner says ‘Barclay was a rare filmmaker, writer, and thinker whose seminal film work makes him a founding figure of indigenous cinema … alongside Merata Mita.’ Fourth Cinema is indigenous cinema and follows on from First being American cinema, Second as art house and Third Cinema as the cinema of the ‘Third World’.

Don Selwyn was an actor, writer, director, narrator, producer and presenter of film, television and theatre. His contributions are often overlooked yet his filmography speaks to his outstanding talents. He is best known for directing Te Tangata Whai Rawa o Weneti – The Māori Merchant of Venice. This was the first feature film entirely in te reo Māori and was based on the 1945 translation by Pei Te Hurinui Jones.

The work and reputations of Mita, Barclay and Selwyn had a huge impact on all New Zealand filmmakers to follow. Lee Tamahori directed Once Were Warriors, Mahana, a range of American action films and the Instant Kiwi ad of the bungy-jumping fisherman. The eight Māori women directors of Waru have acknowledged the influence of Mita and Barclay.

Taika Waititi, Chelsea Winstanley, Ainsley Gardiner and Cliff Curtis have emerged as contemporary Māori filmmakers telling New Zealand stories, notably Two Cars, One Night and Boy. Their combined successes and resonance with audiences in New Zealand and abroad will continue to inspire future storytellers.