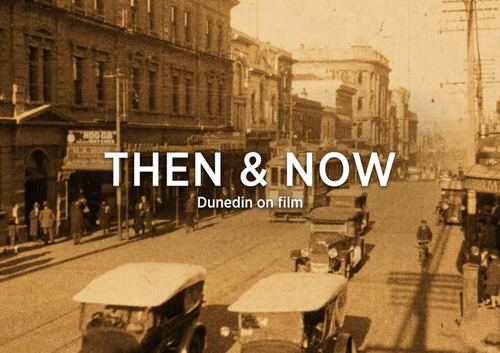

Archives and museums are great at showing changes in a city and allowing audiences to compare the past with their present. Our video series Then and Now – where we recreate shots from archival footage in their modern locations – took a trip to Dunedin at the end of last year and has resulted in a unique look at the city. We catch up with Digital Content Editor Troy Coutts.

More than a century of changes in Dunedin can be seen on screen when we compare old and new footage. Like the other videos in this series, plenty of planning was required to choose historical footage, best navigate the city and pinpoint the filming locations. For this video, Troy Coutts first had a chat with the Ngā Taonga film preservation team, who had recently completed work on Dunedin City from 1926. This film takes a tour around the city, and the new scan looks great and formed the centrepiece of the project. A range of other films from 1912 to 1955 filled out the mix.

This was Troy’s first visit to Dunedin and his trip was preceded by much more planning and research than most people would undertake. This involved plotting locations on Google maps, cross-referencing with Dunedin Heritage and collaborating with Seán Brosnahan, curator at Toitū Otago Settlers Museum. ‘Seán was really keen right from the start, we had a video meeting and exchanged emails. I gave him our brief and talked about ideas, and we later met up when I was in Dunedin – he was very helpful and accommodating.’

Having a local perspective was invaluable and Seán had an incredibly rich understanding of the city. He provided fact-checking and explained the prior uses for different buildings, and the city as a whole. ‘He also gave plenty of context and local colour. He knows not only the changes, but also understands why things took place,’ says Troy. ‘It made the whole Dunedin project a great one.’ Troy found the changes in the transport hub of the city over the decades particularly interesting – the centre being initially based in Princes Street before shifting to the Octagon in later decades.

An example of Troy’s research – matching a frame from The Land We Live In (Ref F11142) to a Google Maps Street View.

Material and expertise from Ngā Taonga and Toitū were combined to form a richer picture. Toitū had stories and exhibitions about many of the buildings and locations featured in our film footage. The city’s residents are able to visit and experience the changes. Seán also has experience with exhibitions that compare old and new images of Dunedin. Displays such as this had originally led to Troy’s original concept for these Then and Now videos. Not finding many examples online, he worked with the wider Share and Promote team at Ngā Taonga to bring the series to life.

Differences on the streets are immediately obvious when one watches the video. Many of the buildings had not changed much from how they looked in the archival film. It meant that in many cases, they became less of a focus, bringing everything else to the front. ‘You see how people decorated the street, what they drove, what they wore. Seeing more populated streets was a cool and surprising outcome from this project.’ Initial reactions on our Facebook post of this video similarly pointed out how few people were on the streets in 2020, and how the early crowds seemed to have been replaced by cars.

Once the filming locations had been confirmed and Troy was on the ground, he found there were lots of signs and plaques in front of buildings. ‘So much of the location planning happens on Google Maps, so it was nice to have the confirmation that I was in the right place. I could also tell the city really cared about its heritage.’

Troy set up his camera and placed an iPad beside the viewfinder. The iPad played the archival footage and Troy would mimic the shot, doing his best to correctly match the frame or the speed of the pan. In addition to trying to figure out where the filmmaker was standing, Troy was also unsure about the camera setup they would have used – different lens leading to different looks. ‘I take multiple shots at each location to give myself the best chance that one of the shots I recorded is reasonably close to the ‘then’ footage.’

It wasn’t until he was in the editing room that he could really tell how successful he was. The ‘then’ and ‘now’ scenes were overlaid and Troy switched between the two to get the closest match possible – it’s like putting a puzzle together. ‘There are some minor misalignments,’ he notes, though overall the results are pretty impressive. ‘There was one cinematic scene at Otago University, with the sun going through the courtyard – a really glorious angle, plus there are students and professors. I messed up the angle though. I thought it was dead centre in the archway but it’s actually much further left. It looks different, but it’s still interesting and definitely one of my favourite shots.’

Putting everything together with modern equipment is a luxury that filmmakers of the past may not have imagined. ‘Having digital freedom is nice. I shoot in 4K, and I don’t need to use the whole frame of what I shoot. I make the frame a bit wider, and can then zoom in and won’t lose too much quality.’ There’s an extra 20 percent that’s available. Troy then matched the new footage with the archival footage, setting it to the original 4:3 ratio frame, not widescreen – he can modify the material he shoots but not the original.

While past filmmakers did not have the digital flexibility Troy has, could he relate to what they may have experienced? ‘I do wonder what it would have been like for them. It’s a totally different feeling now, especially with how people interact with cameras. Many people on these old films stare at the camera and seem confused.’ They also sometimes look to the side, presumably at the camera operator manually cranking the film. ‘I do find myself staring at people staring back: what were they thinking?’ Nowadays, with cameras such a part of our lives, Troy finds people just walk past, cross the road or look down while he films. ‘It could be quite nice to have people stare’.

However they interact on the streets, there’s little doubt that people today viewing this material will be drawn to the screen, looking at the many changes that have taken place on the streets of Dunedin Ōtepoti.