By Rebecca Chrystal (Intern - Victoria University Wellington Pasifika Studies)

'The Pacific Prepares for War' is a film, with footage of the NZEF preparing to invade German Samoa in August, 1914.

It starts with two ships docked in Wellington Harbour and Mount Victoria can just be seen edging into the background of the first shot. The S.S. Monowai and the S.S. Moeraki are troopships and at the bottom of the second frame is a large, 12-pounder artillery gun.

Framed against the outbreak of the First World War, these ships were involved in the conflict but weren’t on their way to the Northern Hemisphere. When war was declared, the nation of Samoa as we know it today was under German administration and New Zealand, being the nearest of the British Empire with enough forces, was tasked with securing the colony. It was unknown what kind of defence German Samoa would put up, and preparations for combat are evident from the presence of artillery. But the outcome was fortuitous, as the small German administration surrendered without a single shot fired. Gallipoli is remembered in the New Zealand psyche as our baptism of fire, but our first action as a nation in the First World War was invading our Pacific neighbours and despite protest holding them under New Zealand administration until 1962.

Our Anzac Sight Sound online exhibition is fortunate to have access to a number of items that outline preparations for the First World War within the Pacific, as well as the contribution made by a number of Pacific nations. Niue and the Cook Islands for example were under New Zealand administration at the time and wanted to contribute men to the war effort. The offer was initially turned down, but due to the massive loss of troops from the Gallipoli campaign they were allowed to join the 3rd Māori Contingent of reinforcements for Te Hokowhitu-a-Tū – The Māori Pioneer Battalion.

Some of these Pacific volunteers can be seen in century old footage as they march down Lambton Quay in 1916, and it is touching to see a boy on the street press something into the hand of one of the soldiers. These Pacific troops would go on to face conditions far harsher than they ever imagined and more than 80 percent of the Niuean troops became so ill that they had to be hospitalised at a convalescent camp in Hornchurch, Essex. Local villagers were so moved by these soldiers from the other side of the world that they donated what little fruit they had to help substitute the Niuean diet.

A moving audio recording in the exhibition is a Niuean song entitled “Lologo tau kautau Niue ne oatu he Felakutau Fakamua he Lalolagi”, which was originally sung by those Niuean volunteers. They sing “We’re here to join forces with you / We will go to battle together / We hope for victory / Before we return to Niue / To Niue, to Niue our homeland.”

Of course, we often forget that Britain was not the only empire calling on troops from the Pacific during the First World War. The French had been on the frontlines of the First World War and called for volunteers in their colonies of Noumea, the Loyalty Islands (both now part of New Caledonia), and Tahiti (known as French Polynesia). The war for these soldiers was a lot closer to home than you might think: the port of Papeete in Tahiti was attacked in 1914 by German armoured cruisers.

Footage from the National Film and Sound Archive of Australia shows French Pacific troops on parade in Sydney in 1916, as well as 300 more volunteers passing through Sydney again in 1917. The later footage is particularly emotional, as it shows these troops playing on swings and seesaws in a park, waving handkerchiefs to the camera. This may have been the first time that these Pacific soldiers had ever come across a playground, but their enjoyment of this carefree downtime begs a heart-wrenching question: how many of these men would still be alive in a few months time, and what horrors would they see?

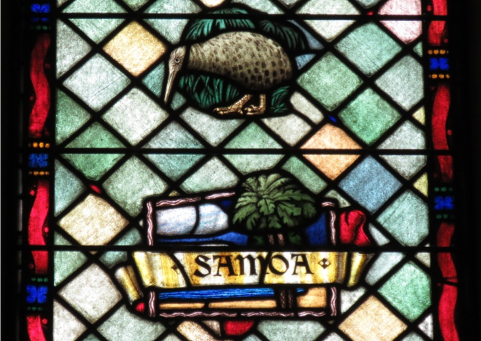

Hero image: The stained-glass window in the Hunter Building of Victoria University of Wellington - identifies all the locations New Zealanders fought and occupied in World War One, including Samoa.