Written by David Klein.

The 'World War Two New Zealand Mobile Broadcasting Unit Recordings' collection has been recognised as being of significant international documentary heritage. The inscription is also a recognition of the invaluable work done by Ngā Taonga. This story covers the digitisation work for parts of this collection. Read more about the inscription.

Imagine it’s the early 1940s and an Army truck crosses the sands of Northern Africa, comes to a halt and is set up on jacks. Microphones with long leads stream out of the truck and over to a line of New Zealand troops serving in World War Two. They’re waiting to record simple messages for the National Broadcasting Service Mobile Unit to send back to loved ones and the rest of the country.

The recordings are cut to a disc on a recorder in the truck, to be sent back to New Zealand for broadcast. Now, nearly 80 years later, several boxes full of them are in the office of Sandy Ditchburn, a Senior Sound Archivist at Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision. Her office is filled with audio recording and digitisation equipment and she is working on a project to digitise these discs, to make them available now and for future generations. Among the many fascinating recordings on these discs are talks by soldiers and officers about their experiences, historic ‘Action Despatches‘ (correspondent’s reports from battles such as El Alamein and Monte Cassino) and hundreds of short poignant greetings to parents, wives, sweethearts and mates back home.

Hero image: Sandy Ditchburn working on a U Series disc (Photo by David Klein)

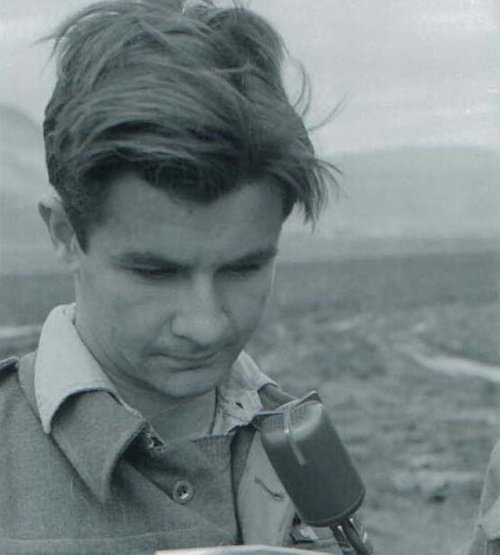

Flight Sergeant Alan T Condon, the last man heard in the recording below - Courtesy RNZ Photographic Collection. (Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision)

Archibald Curry introduces short personal messages from New Zealanders stationed at Monte Cassino.

This collection of recordings from World War Two is known as the ‘U Series’ – strangely, the ‘U’ stands for ‘European’. There are similar collections from different theatres of the war: the P Series for Pacific and the J Series from Japan. The U Series is one of the most extensive archives of audio recorded in a World War Two battle theatre that exists anywhere. Ditchburn explains the National Broadcasting Service had started using disc-recording technology in the mid 1930s and they wanted to send it overseas to cover the war.

“I love the U Series. I think it’s really interesting,” she says, “and it’s so important. It’s about New Zealand servicepeople, made by New Zealanders, for New Zealanders. It was the first time Kiwi broadcasters accompanied troops. It includes a lot of Māori Battalion Recordings.” The U Series is hugely important to historians and the family of those who recorded messages. “We quite often have whānau contacting us. We’re told things like ‘I’ve heard this audio from you and my children have listened and they can hear the voice of their great grandfather for the very first time.’ It’s really significant and beautiful for them.”

She pulls out a couple of pictures showing the Unit. It was housed in an Army Bedford truck and would travel around and make on-site recordings on disc, a system which was later used after the war, back in New Zealand. “The studio body and its three-man crew were shipped to Egypt with the 2nd New Zealand Expeditionary Force in August 1940. The body was attached to a truck chassis and it then travelled around the Middle East, the Mediterranean, North Africa and later to Italy. They got stuck in the desert sand quite a bit – it sounded like they really struggled.”

Archibald Curry (NZ Mobile Broadcasting Unit) - recording a message from a New Zealander on the Cassino Front, 1944. (Courtesy Alexander Turnbull Library)

Despite some of those challenges, an enormous number of Mobile Unit recordings were made over several years. More than 1,400 discs were produced, with each side containing up to ten minutes of sound material. Due to the secrecy of the war, everything had to go through a military censor before the final recordings were made. “Anything that was seen as giving up a location or any sort of plans, you just couldn’t talk about in case the enemy was listening – sometimes not even the names of soldiers,” describes Ditchburn. “So they might say ‘you’ll all know the voice of this man from Whanganui. He’s here to talk to you about this and that’.” The personal messages were scripted, checked and then read aloud by soldiers, nurses and support personnel who had been lucky enough to be chosen to make a recording, through a ballot system. Though these recordings were carefully reviewed and vetted, the strict measures resulted in a warm and sure delivery.

Mobile Unit Broadcaster, Doug Laurenson, reflects on the recordings.

The recorded discs were then shipped back to New Zealand, which took up to ten weeks. “The recordings were broadcast on radio as a programme called With the Boys Overseas and were really popular,” says Ditchburn. “They were played on the National Broadcasting Service on Sunday night and then repeated on Tuesdays because everyone loved hearing them so much. Listening today, they’re a product of their time. Some of the language sounds a little bit racist, or a little bit sexist to us today. It’s still a really great snapshot of what was happening over there, though.”

Hearing the voice of a loved one serving overseas must have been incredibly reassuring for families back home. Sadly, when the discs finally reached the Broadcasting Service in Wellington, a staff member had the grim task of checking the names of those who had recorded messages against the military’s death and casualty lists. If the man had been killed in the months since recording his message, his disc was pulled and not broadcast, but it is believed his family was notified that they could come and listen to the recording in private.

The U Series collection captures life told from the perspective of those who lived it, which is so important for us today. “We learn so much from history that shapes who we are now,” reflects Ditchburn. “When you hear the voices, it’s so real and you can think: ‘war sounds horrible: we shouldn’t do that again’. We learn from the past to make the future better.”

The discs themselves are often revealing. Lifting one from the crate, Ditchburn points out labels and markings on the surface. “Occasionally a disc label will say ‘Not For Broadcast’: it contains material that hadn’t been approved by the censor,” she explains. “Some of these records may never have been heard since.” These physical objects can also show additional personal touches from the engineers who created them. “A wax chinagraph pencil was often used for notes and basic editing. Different lines indicate cuts, or it’ll read ‘don’t play this’ or ‘start here’.” Some of them are covered in chinagraph pencil, “which is a pain because it doesn’t make for easy digitising.”

‘Dead’ or ‘Dud’? - The challenges of looking back in time. (Photo by David Klein)

Digitising the discs in this collection is a major project for Ditchburn. “Most of the U Series is recorded on these 12-inch lacquer discs,” she explains as she places one onto a turntable. The label provides basic information and there are a number of written notes scrawled across the black surface. This disc has an aluminium base with a nitrocellulose lacquer poured on top. “To record the audio they just cut into the lacquer. The recorder had to be perfectly level for this to work properly, which is why the truck had a number of jacks to stand on.” No one could enter or leave the truck while recording, explains Ditchburn. Sometimes there are mistakes or some of the grooves have nothing recorded in them, hence the wax pencil markings.

Broadcaster Noel Palmer inside the Mobile Unit truck - Courtesy RNZ Photographic Collection. (Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision)

It must have been a tricky operation. “There’s a disc which has a steel base – it was really heavy, about 600 grams (three times as heavy as an average 200-gram disc). Unfortunately it was cracked and broken. The metal wasn’t affected, but being metal, it expands and contracts with heat. These changes can cause the nitrocellulose layer to shrink and crack. Very occasionally the base of the discs is made of glass!” exclaims Ditchburn. “They had to get creative because metal was a precious commodity during the war.”

It’s important to remember that these recordings were made near conflict. On some of the correspondent’s reports, aircraft, gunfire and explosions can be heard in the background. The disc recording process works well, but it was often done in less than ideal circumstances. Adding to the danger is the material itself: nitrocellulose is flammable. Ditchburn describes how she’s heard “that the disc could get really hot when they were being cut. The little cut bits would come off and if they got caught under the cutter they could actually heat up and catch fire.” She points out a picture from inside the truck showing a fire extinguisher wisely placed immediately above the recording space.

Archibald Curry’s Action Despatch No. 3, Cassino, Italy.

Another problem archivists face when dealing with these discs is that over time, the lacquer can exude palmitic acid, which is a waxy white substance. Because it’s acidic, it eats away at the lacquer and ruins the grooves and causes distortion that isn’t reversible. “This is the most fragile sound format that we have in the collection,” says Ditchburn as she grabs a technical manual. “The International Association of Sound and Audiovisual Archives says that all formats are at risk and need to be preserved as soon as possible. But lacquer discs are the number one priority because they’re so fragile. And these are from 1940 – they were never intended to be archival. The fact that we have them at all is amazing!”

This valuable series has already been preserved twice before by earlier sound archivists. In the early 1990s the discs were copied to digital audio tape – and then in the early 2000s to CD. Both formats were the best available at the time, but both have since proved unstable. Digitising the discs is the current international standard for audio preservation.

Ditchburn is working against time to preserve these discs. And due to so much time passing since they were made, it can be a challenge to figure out exactly what each recording contains. “They’re all in their old sleeves which is an acidic paper and it’s not great for the discs,” explains Ditchburn. “I’ll take them out of their sleeve and assess both the sleeve and disc for any extra information. A disc might say one thing and actually it’s another. Figuring that out is almost half the fun.”

A 'U-Series' disc - the white marble pattern is palmitic acid. (Photo by David Klein)

Before the discs are played so they can be digitised, they’re cleaned – a very important process. Ditchburn later describes how difficult it can be to clean them if they’re damaged. Ngā Taonga has an ultrasonic cleaner but putting a disc in there in some cases may be more damaging. If there’s palmitic acid, ammonia hydroxide is used to clean it off. Then it goes on a Keith Monks machine – a special vacuum cleaner for discs that removes dirt and water. The disc then goes into a new archival sleeve and bag, then it’s ready to be recorded.

Ditchburn chooses a needle stylus and gets the disc spinning on the turntable. “I have a whole different set of styli, with different-sized needles for different discs,” she explains. “Sometimes they were recorded with different groove thicknesses and it’s good to play around a little bit to make sure I record the best quality with the least distortion.”

A crate of 'U-Series' lacquer discs - on the left are in new, archival sleeves and bags, while the ones those on the right, are still currently in their original sleeves. (Photo by David Klein)

“Most of the discs are 78 RPM and I play them in real time while using a converter into Wave Lab to get it digitised and onto the computer.” The needle glides carefully through the grooves of the disc. “I don’t edit the audio,” says Ditchburn, “it’s exactly as it is on the disc, which gives a complete snapshot. It’s really important to go to the original and get them done at the highest quality possible.”

A whole pattern of squiggly lines dances across Ditchburn’s computer screen. The audio data is being copied from a precious but incredibly fragile disc to a new home where it will be stored digitally and be backed up in numerous locations. The disc itself will be kept in a climate-controlled vault.

There’s no doubt that this is a special collection of recordings from people at war far away from home. The fact that the discs still exist and are in the Archive is remarkable. Ditchburn is getting ready to work on the next disc in the collection, making more and more of them available to hear online. Descriptions of each disc can be found on the Ngā Taonga online catalogue and the audio can be uploaded to each entry if requested, as Ditchburn’s work progresses.

So thinking back to the 1940s in Northern Africa, the Mediterranean and elsewhere, soldiers and other personnel were queueing up, patiently waiting for their turn to record a precious message for people in New Zealand, half a world away. They’re excited to get in touch… even if they know their voice recording won’t be broadcast for a couple of months. How many of them would’ve thought then that these recordings would be heard by their descendants again decades into the future?

Hear broadcaster Noel Palmer reflect on these recordings.

Many thanks to Sandy Ditchburn and Sarah Johnston for their time, knowledge and assistance writing this article.