The 1981 Springbok Rugby Tour of New Zealand was a fractious time in the country. The definitive protest documentary was 1983’s PATU!, which screened at the New Zealand International Film Festival. For the fortieth anniversary of the Tour, Ngā Taonga staff spent nearly five years working on the film’s preservation, and comparisons with earlier transfers reveal an impressive level of detail.

But how much work is too much? The technologies available to restore and improve films are amazing, but it is possible to go too far in pursuit of perfection – as Star Wars creator George Lucas reflected after watching a preview of one of his films.

There are several ‘-ation’ words in the archiving world: preservation, restoration and conservation. These terms can mean different things in different contexts, and they can overlap. While it’s easy to get hung up on what each means, as an archive, they’re all important to the work Ngā Taonga does. Whatever form it takes, we’d like our work to be invisible; if the original filmmaker were to see it, they’d say ‘that’s my film’.

Preservation generally means creating an accurate record of what an artefact looks like, through making a scan or a copy. That’s an important process and there are archival standards that we follow through organisations of which we’re a member – though it isn’t always as straightforward as you might think, explains Ngā Taonga Film Preservation Manager Dr Leslie Lewis. ‘Should it look like the artefact as it is now, or should the goal be to match the appearance of the film when it was first released? And crucially, do we know enough to make that determination?’

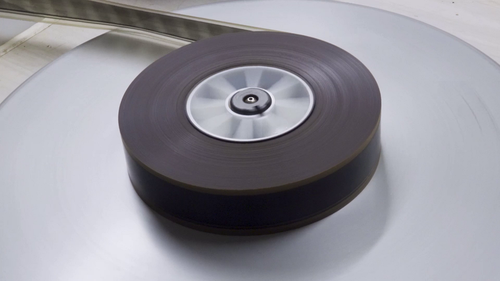

Reel of film on a winding table.

There are a range of things to consider with a preservation project: the age of the film and the wear or damage it may have had prior to being in the Archive; how the film would have looked to audiences at the time; format changes that occur during an analogue to digital scan; and quality control and philosophical discussions to combine these together.

Another path might be restoration. This also has a range of options and approaches but will involve familiarity with the physical characteristics of a type of film and how those change over time, and an understanding of contemporary titles and styles from the time of release. It may involve reconstructing a title from multiple elements and examining multiple sources, such as viewing prints, to gain as much information as possible before making decisions.

Hear more about this work on RNZ’s Standing Room Only.

‘In an ideal world there is a completely accurate original release print – with no damage, colour fade or other signs of aging – that can be applied to new scans of the high-quality master material in order to recreate the original “look”,’ says Lewis. Having that information is important, as it respects the intentions of the original filmmaker.

Without these groundings and considerations, you could make whatever changes you wish. At an extreme end of what’s possible are the impressive technical feats computers allow us to perform. On YouTube you can see 120-year-old film that has been colourised, stabilised and ‘up-scaled’ to 4K.

Within Ngā Taonga this video would be considered an entirely new work. And while it’s impressive, it isn’t true to the artefact. To quote Jeff Goldblum’s character in Jurassic Park, ‘Your scientists were so preoccupied with whether or not they could, they didn’t stop to think if they should.’

The Ngā Taonga film collection is composed of hundreds of thousands of recordings from thousands of sources. Each of them has a unique journey prior to being in our vaults. While some are relatively new, or have been well-kept by film enthusiasts, many spent decades in a garage or attic, in far from ideal conditions. Once they get to us, their condition is assessed and they are rehoused: in an appropriate archival container (like a film can) and in an atmosphere-controlled vault. These are standards based on work by audiovisual archivists and material scientists to determine the environmental conditions (temperature and humidity) in which to keep different types of audiovisual material. This serves to extend their lifespan as long as possible and give archivists time to preserve them.

Film Preservationist Richard Falkner working on a film.

This forms part of our crucial conservation work. Our colleagues at the NFSA (National Film and Sound Archive of Australia) define conservation as work ‘to ensure the continued physical survival of an artefact without further degradation’.

This re-housing can be considered passive preservation; active preservation can include repairing broken splices, perforations, and edge damage, cleaning the film, and other steps to allow a new print or digital scan to be made. This story covers some of the work undertaken on the very oldest film in our collection.

It’s important to note that though some repairs to allow the film to move through preservation machinery may be carried out, Ngā Taonga doesn’t ‘fix’ films. Marks that were present in the original are left in. Dirt or debris present on the edge of the frame – like in some PATU! scenes – is retained (and not digitally erased), as this is how the film would have been presented to audiences originally. Such imperfections reflect the equipment and filming conditions (such as light levels for exposure) that were available at the time.

In our preservation work, Ngā Taonga generally tries to make a film look as close as possible to what audiences would have seen at the time. Lewis notes that cases where we don’t ‘may be because we’re unable to fix issues without creating digital artefacts, or because there isn’t enough evidence for us to be confident that we are correctly emulating the original, and not just guessing.’

In addition to repairing parts of the physical film, with a scan this may involve stabilising the frames, or addressing damage or scratches to the print that occurred after the film was released. Another step is colour grading. Grading can alter the colouration of a scene and is used to ensure the look of the film is consistent, that things like skin tones are accurate, and again, closest to what audiences would have seen at the time. It can also extend to considering the warmth of the projector bulbs used at the time the film was made – very old tungsten filaments produced light spectra different to a Super 8mm projector, which differs again to xenon bulbs in a modern digital cinema.

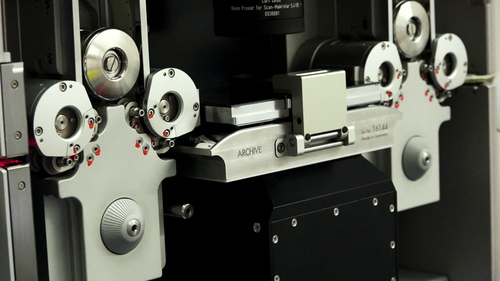

Much modern film preservation uses a scanner to make a digital copy, a process that changes something you can hold and see with the naked eye into a collection of 1s and 0s. ‘You’re fundamentally changing the artefact and the experience of it,’ says Lewis. ‘When this transformation happens, we have to be incredibly careful not to introduce any changes through the scanning process – either through introduced digital artefacts or aesthetic decisions not based on evidence.’

Close up of the ARRI Scan.

An important part of this scanning process is quality control (QC) screenings. The scanning process can very rarely add or remove frames, or introduce digital glitches or artefacts. The team watches the scanned films to catch any errors, which can then be corrected – either by re-scanning or re-rendering the affected section of the film.

The individual tastes and choices of film preservationists may be at odds with decisions made by the original filmmakers. How did they intend it to look? For a film more than a hundred years old, we rely on all the information we have in the hope of producing something as close as possible to what audiences would have seen at the time.

With PATU! we worked with some of those involved in the film, including editor Annie Collins, coordinator Gaylene Preston, and the whānau of filmmaker Merata Mita. Their insights, the original production notes from the film and the expertise of our film team helped guide the preservation project, so that we can honour the intentions of those who made the original.

The team discusses what work needs to be done on a film, but the consideration is always the same – working on the film in a way that is invisible, to create something that the original audience would have seen, and that the original filmmakers could have created using the technologies of the time.

By following archival standards and making well-considered choices, the staff at Ngā Taonga ensure that an accurate record of each artefact is made, and that these will last for decades into the future.