Check out the first installation of the is blog, 'Chasing the White Whale' - The Saga Begins...'.

Thanks again to Lindsay for allowing us to publish this fascinating investigation.

Chasing The White Whale: The Mystery of the Missing Whangamumu Whaling Film (Part Two)

How did Woodard know to contact Herbert Cook? Possibly through a marine scientist. Herbert Cook was regarded as an expert in Bay of Islands whaling and the Discovery Reports, research papers from the scientific RRS Discovery expeditions of the mid 1920’s, say that the Bay of Islands whaling section ‘is compost almost entirely from conversations with Mr H. F. Cook manager and part owner of the station at Whangamumu, who visited the RRS Discovery at Auckland…’.[11]

Another possible scenario, and this is conjecture, is that Zane Grey told him of Cook and Whangamumu. Grey ‘big game’ fished at the Bay of Islands and on the northern New Zealand coast in the summers between 1926 and 1928, and notably, in the summer of 1933 during which ‘a motion picture of mako shark fishing’ was made.[12] Grey was very involved with the movie industry.He does seem to be referring to Herbert Cook when he writes ‘…during our stay at Russell there was a small whaling steamer there. The captain had fished with the New Bedford and Nantucket whalers in those early days’.[13]

Grey’s popularity in his 1920’s heyday overlapped a boom in the motion picture industry and there was fierce competition for movie rights to his books at this time. He certainly knew people in the film industry and must have been aware of the Whangamumu Whaling Station. In part because of Zane Grey, by the early 1930s, the Bay of Islands had become world famous amongst wealthy fishing aficionados as a big game angling ‘El Dorado’.

The film project was a huge undertaking, especially for a world still in the grip of the Great Depression. Researching and then arranging the initial contacts with an isolated place in distant New Zealand would not have been easy. The cost of transport from America, and accommodation for Woodard and his wife, the building and freighting of the whaleboat, chartering a motor ‘camera launch’ and employing Herbert Cook and the whaleboat crew for some eight weeks as well as the costs of shooting and developing the film. Presumably the film was developed in the United States. How was this venture financed?

The Whale is attached to whaleboat, with the tail very close - this is a very dangerous position, as the tail can smash the boat, and the men in it. (Photo - Stacy Woodard 1933)

It was the intention of Stacy Woodard “to embody the whaling pictures in a film with considerable dramatic interest – which in due course [will] be exhibited in New Zealand” and his motivation seems to have been as a part of the entertainment industry rather than as a scientific recorder of nature or history.[14] Curiously, after having just arrived in Auckland, he advertised in the New Zealand Herald in late August 1933 ‘Wanted. To take part in motion picture. Man 23 to 30, about 5ft 10” 160lbs. Previous dramatic experience necessary. See Mr. or Mrs. Woodard. Central Hotel’.[15] Presumably such an actor was to have taken a part in the soon to be filmed whaling movie. That would have been a demanding role.

Woodard moved onto other projects, including the one that won him his Oscar. He was an uncredited contributor to King Kong (1933) and was involved in the filming of Pare Lorentz’s American classic The River (1938). His whaling film was never completed and Stacy died of a heart attack in New York in 1942. Herbert Cook died in 1934, the year after the Whangamumu filming, and is buried in the graveyard at Christ Church, Russell.

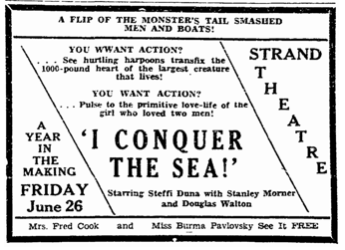

A total of some seven and a half minutes of the Whangamumu film was used in the 1936 low budget drama, I Conquer The Sea, distributed by Academy Films, a ‘Poverty Row Studio’ that produced so called ‘quickies’. The film claimed to have been shot on location ‘in Newfoundland where the action of this story is laid – and to our intrepid crew and cast who spent one long hazardous year ‘a-hunting whales’ to complete this production’.[16] Well it was Hollywood, and who would know the Whangamumu coastline in America? Along with using Woodard’s copy the filming location was most likely Laguna Beach, California. Initial working names were said to be Sea Bandit and Thrill of a Century.

Probably in an attempt to link the film with legitimate whaling history, it had its premiere at the Empire Theater, New Bedford, Massachusetts on 16 January 1936. As such it was the last gasp of well over a century of sometimes close and extensive whaling connections between New Bedford and the Bay of Islands. Herbert Cook himself embodied that connection, having lived in New Bedford in 1880, arriving and leaving on a whaleship. Surprisingly ‘The screening made almost no splash in the local newspapers; the New Bedford Mercury didn’t even bother to print a review’. Reviews that were given were mixed, ‘a crudely drawn affair’; [17] ‘the plot does not help matters appreciably…there are any number of technical faults’ [18] but mention is later made that “The film works well because the stock footage of whaling (Woodard’s film) is integrated extremely well into the film…Incredibly exciting shots of whaling remain stunning.

I Conquer the Sea also distinguished itself by being the first starring role of the 1940’s Warner Brothers heart-throb Dennis Morgan – he later played opposite Doris Day and James Cagney; and with Ginger Rogers in Kitty Foyle (1940) (she won her Oscar for her role in that film). Morgan was known by his real name of Stanley Morner in I Conquer the Sea.

Lurid advertisement for 'I Conquer the Sea'. (Marietta Journal, page one - 25 June 1936)

The movie seems to have largely sunk without trace soon after release, becoming part of that extensive genre of ‘Forgotten Cinema’. In the late 1930’s and 1940’s it was reduced to second billing in sleazy 24 hour picture theatres. Woodard was not acknowledged in the film credits and the film never screened in New Zealand.[19] An interesting aside is that in 1951, Variety magazine wrote that ‘writer Richard Carroll claimed that this film [I Conquer the Sea] was based on his story Storm in Their Hearts and that Carroll was suing for distribution rights to the film…’through an agreement with Academy Pictures all rights reverted to him in 1946’.[20] The outcome of this legal challenge is not known.[21]

Harpooned whale diving - note the two whale-lines, attached to the whale and to the boat on right of photo. (Photo - Stacy Woodard, 1933)

Whaling from an open boat involved first catching up to the whale, harpooning it and then tiring the whale with the boat being dragged, often at speed until the whale slowed. The whaleboat was then physically pulled up to the whale and the whale lanced and eventually killed. The dead whale was then rowed back to shore and ‘cut in’ and the oil extracted. All these are shown in the short sequence of film that has been found.[22]

These moving pictures taken 81 years ago at Whangamumu are a unique record of small boat whaling, out-moded, even when the techniques were resurrected through the skill of Herbert Cook, in 1933. The films are a taonga of our past showing not only our people, but also a resonance of a whaling culture that has long gone. However they are more than this, for these images are also a requiem to small open boat whaling worldwide. As can be seen from the stills taken from the short sequence that I have found, as Woodard stated, these are some of the most dramatic whaling film that has ever been taken. As such they are of international significance. They are absolutely unique. Their like will never be filmed again.

As the reels of film taken at Whangamumu almost certainly returned to America with Stacy Woodard, if they survive they are hopefully lying forlorn and forgotten, and if the provenance has been lost, unidentified in some American archive. They were undoubtedly taken on the old nitrocellulose type of film and will be deteriorating by the year. We must find them!

Footnotes for Part Two:

[11] F. D. Ommanney, Discovery Reports Vol 7. Whaling in the Dominion of New Zealand, University of Cambridge, 1933, pp.239-252.

[12] New Zealand Herald, 14 February 1933, p.10. Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision holds a number of films that features Grey: Deep Sea Fishing – Bay Of Islands (1927), ref: F8180, Deep Waters (1929), ref: F40217 and Deep Sea Thrills – Swordfishing In New Zealand (1934), ref: F8181.

[13] Zane Grey, Tales of The Angler’s Eldorado, New Zealand, The Derrydale Press, 2000, p.27.

[14] Boese states that the film “was used to make a motion picture film named ‘Whaling as in the Olden Days’”, p.377. No evidence of a film published with this name has been found. See also ibid pp.60-61.

[15] New Zealand Herald, 21 August 1933, p.1.

[16] Onscreen forward to I Conquer The Sea.

[17] Plain Dealer (Cleveland, OH), 28 March 1936, p.16.

[18] Boston Herald, 7 March 1936, p.16.

[19] Stacy Woodard was acknowledged in his New York Times obituary as having “taken the whaling portion of ‘I Conquer the Sea’”. New York Times, 28 January 1942.

[21] The legal challenge may have been initiated because the film was going to be shown on television. A resolution may have been reached, as it was shown on TV in the early 1950’s. See Plain Dealer (Cleveland OH), 18 May 1951, p.8 & 19 February 1953, p.14.

[22] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6jJUVo67E8U

© Lindsay Alexander, 2014.