Image: Nanook of the North poster

By Jakki Galloway

As part of The New Zealand Film Archive’s contribution to the WWI Centenary, my head has been down writing an NCEA resource based around some of the war documentaries we hold in our collection. The resource focuses on an analysis of the codes and conventions of documentary making, and discusses how these conventions have developed and changed over time. Some of my rediscoveries have been fascinating:

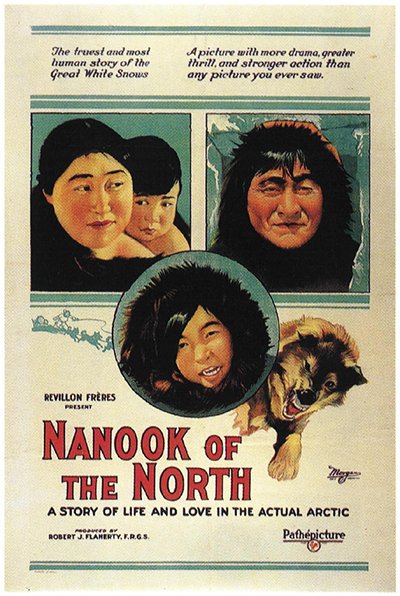

The earliest films did not delineate between fiction and non-fiction and “fakery was not seen as deceit but as enterprise” (Ruby, 1980). In Nanook of the North (1922), by Robert Flaherty, reconstructed scenes add drama and narrative to the storytelling. The conventions Flaherty used were those of fiction. An outsized igloo was built so that camera equipment could fit inside. This proved too dark so half of the igloo was removed to let the light in. (Ruby, 1980)

Advances in editing techniques split film making in two, and from this documentary was born. British filmmaker John Grierson believed that non-fiction film should be about information dissemination and he used film to educate people about the real world. Drifters (1929) venerated the everyday lives of North Sea herring fisherman, and the viewer’s gaze turned away from the foreign and towards the everyday man. Grierson made voiceover popular using it to add clarity to his message. In Nightmail (1936) voiceover narration by W. H. Auden elevated a potentially mundane narrative about night mail delivery to one that had poetic impact and gave dignity to the profession. (Barnouw, 1975)

The Second World War saw documentary used as propaganda. Leni Riefenstahl was employed by Hitler to create Triumph of Will (1935) – a film about the Nazi Party Congress in Nuremberg – and then Olympia (1936) to record Germany’s success at the Olympic Games. Using nothing but introductory titles Riefenstahl let images speak for themselves. Her films are notable for their use of multiple cameras, tracking shots following subjects, and slow motion camera to highlight movement. Most celebrated was her footage of divers seamlessly slicing through the water. In the USA Frank Capra who had had no previous experience working in non-fiction began a series of films explaining to both soldiers and civilians why they were at war. Disney Studios helped him to animate the graphics in the Why We Fight (1942-1944) series that was dispersed throughout the Allied countries. To show the invading forces of Germany black ink oozed across the map destroying Europe. These years also saw the introduction of magnetic recording. On entering Occupied Europe soldiers were stunned to discover what they had thought were live broadcasts were actually recorded ones. This technological advancement meant improved sound quality and allowed film makers to use music to convey thematic content of films. In Bert Haanstra’s Glass (1958) this is most fully realised. The film portrays the industrialisation of glass blowing: the assembly line fails when a broken bottle clogs the line and the bottles scatter. The film is so synchronised with the sound that “the viewer can hardly escape the sense that the glass blower is creating the music.” (Barnouw, 1975)

After the war a number of experimental documentary makers emerged and created new techniques. George Rouquier’s Farrebique (1946) followed farm life through the seasons detailing its minutia. He sped up the film footage to illustrate the passage of time, like clouds moving across the sky. This has become known as time lapse photography. The use of archival footage also became very popular during this period, mainly as evidence of the atrocities committed during the war. Alain Resnais used archival footage to make Night and Fog (1955), a film that alternated between past and present to describe life in a concentration camp. The Thornikes made Operation Teutonic Sword (1958), where they used archival footage to hunt down living Nazi war criminal Hans Speidel, and documented the process as they went. As technology developed the use of older archival footage became accessible. Silent footage had been filmed at 16 frames a second and was expensive to stretch to the 98 frames (the standard needed for its conversion to post sound era films). An influential example of this is Nicole Vedres’ Paris 1900 (1947), a detailed portrait of daily life in Paris in the years before the First World War. (Barnouw, 1975)

Later, in 1969, The Sorrow and The Pity by Marchel Ophuls examined the collaboration between the Vichy government and Nazi Germany. Archival footage was juxtaposed with contemporary interviews of a German officer and of collaborators and resistance fighters from Clermont-Ferrandt. This has been a popular technique ever since. The voiceover became increasing obsolete. Early observational filmmakers like Dziga Vertov had called to eliminate all narrative devices and point of view from their films. Vertov saw narrative as descendant of the theatre and therefore artificial. The Man with a Movie Camera (1929) presents urban life in the cities Odessa, Kharkiv and Kiev without making any attempt to create a story or have an opinion. By the 1960s the use of the handheld camera became an option as cameras became smaller and lighter. This enabled filmmakers to follow their subjects around more easily which they felt was a more honest interpretation of their subjects reality. This and developments in synchronised sound shooting on location meant that what became known as Direct Cinema had spread throughout the world. Portrait of Osa (1965) by Jan Troell a Swedish school teacher intimately portrays the life of a four year girl. (Barnouw, 1975)

The performative mode of documentary then encouraged a revival of the voiceover. Michael Moore’s blockbuster Roger and Me (1989) shows the urban decay of Flint, Michigan after General Motors closed down several auto plants. Moore uses voiceover in a new and interpretive way acknowledging the subjectivity of his film making process. (Sherman, 1998)

It is only recently that reenactment has reemerged as a form of storytelling within the documentary genre. It had been used frequently in the early days of filmmaking – The March Of Time (1935) was a newsreel series widely criticised for its use of reenactment where events were reenacted by professional actors. One scene showed two well known figures involved in the Manhattan Project (which developed atomic bombs in WW2) shaking hands in the desert after the first successful test. But the shot was actually made on the floor of a garage in Boston. The BBC series The Days that Shook the World (2003) is an entirely reenacted documentary showing the days leading up to major world events. These film makers have argued that in its ability to fill in or explain facts that are not available on film, reconstruction is legitimised. Ryan (2004), by Chris Landreth, is an animated documentary based on the retelling of an interview between Landreth and the animator Ryan Larkin, who was living on the streets of Montreal at the time of their meeting. (Miao, 2009)

While graphics are not new to non-fiction, Winsor McCay used animation in 1918 film The Sinking of Lusitania to illustrate the torpedoing of the Lusitania by a German U-Boat off the coast of Ireland, and The Einstein Theory of Relativity (1923) used animation to explain a difficult scientific equation. The use of graphics has advanced significantly since the invention of the computer: animation, 2D and 3D images (CGI) and interactive technology have been incorporated into documentary. Today animation is also being used to restore old archival material and to fill in gaps in actual footage or reveal truths that are impossible to film. In Waltz with Bashir (2008) Israeli director Ari Folman reconstructs missing memories from his time as a solider in the Lebanon War using animation. Specific online projects are allowing the user to control and interact with the documentary from pre- existing film clips. Man with a Movie Camera: A Global Remake (2007) is a website by artist Perry Bard. People are invited to respond to Vertov’s original introduction and “experiment in the cinematic communication of visible events without the aid of inter-titles, without the aid of scenario, without the aid of theatre” and upload their own footage. (Miao, 2009)

The attempt to represent reality is where Documentary was born. It is through changes in social interpretations of reality and our responsibility towards it, through political and related economic influences, and through developments in technology that are forever expanding the ways we are able to tell these truths, that the impetus to push the boundaries of documentary forward exists.

Hero image: Nanook of The North (Robert Flaherty, 1922)

References

Barnouw E. (1974) Documentary: A History of the Non-Fiction Film. Oxford University Press, New York.

Ruby, J (1980) A Re-examination of the Early Career of Robert J. Flaherty

http://astro.temple.edu/~ruby/ruby/flaherty.html

Sherman, S.R. (1998) Documenting Ourselves: Film, Video and Culture. University Press of Kentucky.

Song, M (2009) The Role of Computer Graphics in Documentary Film Production. Concordia University, Montreal.

Stermitz E (2008) Man with Movie Camera: The Global Remake – Interview with Perry Band http://rhizome.org/discuss/41030/

Zumby, J (2008) Israeli filmmakers head to Cannes

http://israel21c.org/culture/israeli-filmmakers-head-to-cannes-with-animated-documentary-video/