The artwork has now been installed in the National Library following the move last year. This blog shows off the work in its new space and also updates an interview from 2014 giving a ‘behind the scenes’ about how the work came to be.

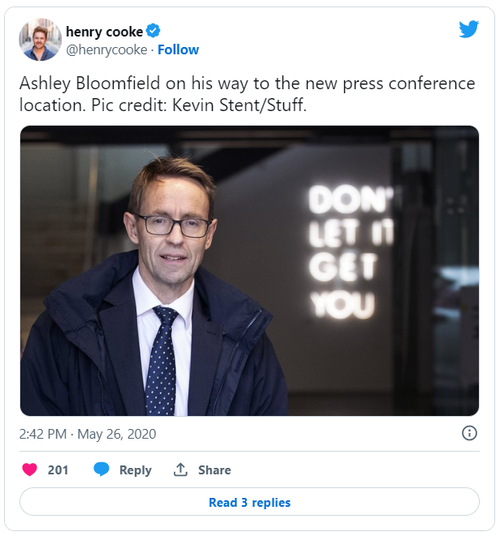

After the move from Taranaki Street, it is now installed in the Lower Ground Lobby of the National Library Building (Aitken Street entrance) and its return after a few months in storage, was welcomed by many locals. It also made an appearance behind one of 2020’s most topical New Zealanders, Director-General of Health Dr Ashley Bloomfield.

Hero image: The 'DON'T LET IT GET YOU' neon installation when it was installed on the ground floor of Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision, facing Taranaki Street.

Nell Williams is a born and bred Wellingtonian who joined the Ngā Taonga Communications Team in August 2014. Like lots of locals, she’d encountered the organisation’s Taranaki Street installation piece many times, and admired the emphatic proclamation of the phrase DON’T LET IT GET YOU, elegantly rendered in foot-high block capital neon letters. Quietly occupying pride of place in our biggest cafe window, the sign is constantly exposed to the usual melee of Cuba Quarter foot traffic, and the weekday rush-hour exodus from Wellington’s CBD to the Southern suburbs. DON’T LET IT GET YOU is easy to admire from afar, accepted as just one of the many quirky artistic markers on the city’s creative landscape.

But once she started working at Ngā Taonga, she saw DON’T LET IT GET YOU every day and realised she’d never really given much thought to what the piece was getting at: what it meant, where it came from. And what the significance was for this organisation. Nell sat down with Diane Pivac, wealth of knowledge on all things relating to New Zealand’s moving image community and Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision’s Head of Audience, to get the story behind the sign.

Nell Williams: So Di, what is the phrase DON’T LET IT GET YOU all about?

Diane Pivac: Don’t Let it Get You is the name of a film made in 1966 by Pacific Films and it’s also the name of John O’Shea’s memoir.

John O’Shea was incredibly eloquent and he had a lot to say… he was Mr Pacific Films, who were the only independent film making company in New Zealand. They kept the idea of independent filmmaking alive basically from the 40s through to the 70s, when The Film Commission was established. And in that time, in the 60s, they made three feature films, one of which was Don’t Let it Get You.

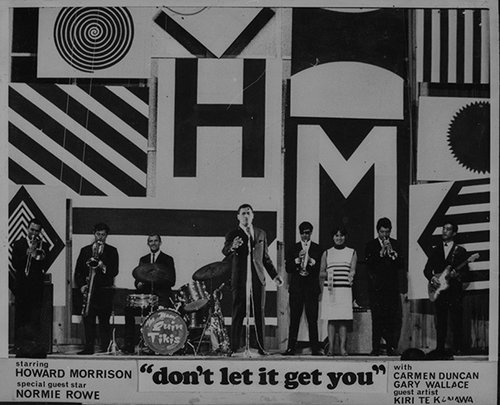

The film is a musical set in Rotorua. It stars Howard Morrison – and Kiri Te Kanawa has a small part in it – and it’s about a music festival. We should have a look and see what John’s memoir says but I imagine the title was something to do with the funding of the film and the circumstances of making the film. There was no money. They found money one way or another. In the film there’s some incredibly funny product placement. And that was all part of getting the film made. I think they went into quite serious debt making the film. And Don’t Let It Get You… I think, the title reflects the fact that John wouldn’t let that stop him.

Poster for the film 'Don't Let It Get You' - Image Courtesy of Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision Documentation Collection.

NW: So kind of a ‘Don’t let the man bring you down’ mentality?

DP: Yeah, absolutely. That’s where I think that comes from.

So that’s the 1966 film. And I think it’s fabulous. We always say it’s ‘filmed in glorious mono’. And of course there’s the title song, the opening song: [sings] ‘Don’t let it get you, don’t let it get you down, go ahead and have a ball’. Crikey.

NW: Catchy as heck!

DP: Ha, yep!

Now Mary-Louise Browne, who is a well-known New Zealand artist, works with words a lot – she made the neon sign. And she’s also a friend of the organisation, so we knew she’d done this piece. And when she first made it, we said “can we put it in our window?” And its been there for a couple of years now.

I’m pretty sure Mary-Louise was inspired by the name of the film and that’s where it came from [for her]. But she’s done some amazing other pieces you might have seen, she starts with one word and she creates artworks where one word becomes another by changing one letter.

NW: Like the steps in the Botanical Gardens?

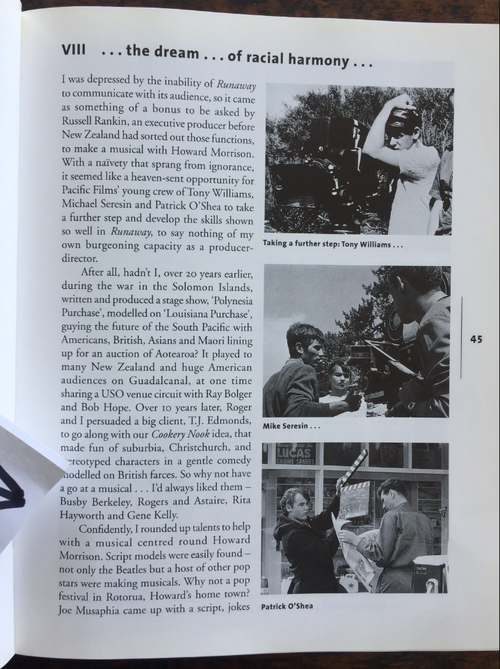

DP: Yes, that’s Mary-Louise. She likes words, she likes texts*. And clearly ‘Don’t Let It Get You’ appealed to her. And to us, too. A New Zealand artist, referring to a New Zealand film and from the film we get to Pacific Films, who were an incredibly important company to New Zealand. Gaylene Preston, when she came back from England, she worked at Pacific Films and as she and many other people have acknowledged, because Pacific Films was operating at a time when there weren’t film schools, it was the unofficial film-school of New Zealand. Geoff Murphy worked there, Gaylene Preston worked there, Michael Seresin¹ [cinematographer] worked there. Seresin was the 2nd AD (on Don’t Let it Get You), and of course he’s now shooting Angela’s Ashes.** Just about anybody you can imagine who works in New Zealand film, if they’re of a certain age, would have worked at Pacific Films at one time or another. So they’re incredibly important to the story of New Zealand film.

NW: That’s a big legacy.

DP: Massive. And John O’Shea was great, he was also one of our founding board members, he was really involved with the archive and incredibly supportive of the work we do. We hold the Pacific Films collection here, which is massive and fabulous – television AND film. They did the Tangata Whenua series, for example, in the 70s. In the 60s, when TV came, the film industry for a moment thought that television was going to be a saviour because they were going to be able to make TV programmes. But at best, they got commercials. And Pacific Films kept on making films right through the 60s, the 70s, the 80s and into the 90s.

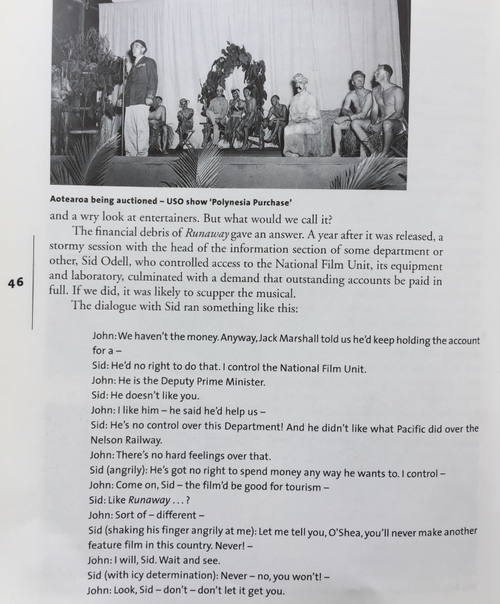

Pages from John O’Shea’s biography, 'Don’t Let It Get You' (Photos supplied by Graeme Cowley).

NW: Where are they now?

DP: Well John died in 2001 and the company kind of stopped with him. They haven’t actively made films for a long time. They just sort of…. ceased to be. And it was really tragic because John’s son, Rory, was a really good cameraman . And he died really close to John and then his daughter. So there was a whole chain of events and I don’t know if that’s what made Pacific stop, but they did.

But those early films… they did a lot of groundbreaking stuff. Broken Barrier in ’52, and then Runaway in ’64 and then Don’t Let it Get You. Those are the only three independently produced New Zealand films between Rewi’s Last Stand being produced in 1940 through to the 70s. Only three films managed to get made. All of them were by Pacific Films.

NW: Wow. That’s huge.

DP: It’s extraordinary. How they did it.

NW: It must have been tough going for anyone to get through one. And they did three.

DP: Really tough. Most people didn’t survive. So yeah, those three, ’52, ’64, ’66. Such big gaps in between. And then nothing. The independent film industry had hardly moved on from the days of the 20s, even though they had bigger crews. Hard yards. And Pacific took on substantial topics, and you can see it in John’s writing, which is really good. He’s got a paper about film at UNESCO. Boy, he had some great stuff to say. And a great sense of humour. And Don’t Let it Get You would have definitely come from those things about him. Not letting things get to you.

NW: Is that what the film’s about?

DP: Well it’s a musical. A guy comes from Australia to play the drums at a festival in Rotorua and he hooks up with Howard and the others. Gary Wallace (the drummer) was a pop star in Australia in the 60s and it’s the usual story – he comes over to the festival and falls in love with a local girl, joins the local band, everything goes well…

NW: “…there’s a kerfuffle, then it’s all right…”

DP: Yeah, you got it. And it’s awesome, Howard Morrison and the Howard Morrison Quartet play in it, there’s a great scene with Kiri Te Kanawa and she’s sitting in a marae with all these little kids around her and she goes “See? Now this is how I sing without an orchestra” and pushes the button on a tape recorder and there’s this beautiful singing and they all go “ooooohh”. Bits and pieces like that which really make it. And as I say, there’s the hilarious product placement. And it got an Australian release which was pretty extraordinary.

Still from the film 'Don't Let It Get You' - Children are transfixed as Kiri Te Kanawa demonstrates how her tape recorder assists her training, a high-tech alternative to an orchestra!

NW: How much do Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision staff know about the sign’s legacy? What comments or questions have you heard from them – or visitors – about what it is and why we have it?

DP: It’s mainly visitors, and the big thing is that we see people taking photos of it all the time!

NW: It’s iconic, at least I think so… for this building, for that corner, for this part of Wellington.

DP: Yeah it is, so we often see people stopping in front of it. But I haven’t heard staff asking too much about it. Though I don’t think many people realise it’s a permanent part of our collection. It’s so GOOD it has a home here.

NW: It’s very positive, sometimes I think “thanks, sign!” But then I also think it sounds vaguely ominous. What is this ‘it’ that is coming for me?

DP: [Laughs] Ah, like late night Cuba Street?! Yeah it’s really cool to see people looking at it all the time, taking photos of it all the time. I reckon it’d make a great postcard. It is, I think, one of the best film titles ever.

NW: It definitely speaks on all kinds of levels. The fact that the sign isn’t a old set piece or prop, it’s a deliberately made piece of art referencing a romping Rotorua based musical from the 60s – that’s extra fun for me to find out.

DP: And now you should watch the film. It’s one of my faves. For lots of reasons!

Notations

- Michael Seresin was the cinematographer for Bugsy Malone (1976), Angela’s Ashes (1999), Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban (2004) and Gravity (2014).