Barry Thomas is a bit of an iconoclast. For more than 40 years he’s been involved in art, filmmaking, activism and community integration. You’re probably familiar with some of his work whether it’s on the rugby field, on a vacant lot or on the small screen with productions like rADz. As part of our TOHE | PROTEST exhibition, we met with Barry to hear about his exciting career in film and activism.

It all started on the golf course. Barry Thomas’s dad played a few rounds with producer and director Stan Wemyss, and asked if Stan could get his then-16-year-old son a job. Barry found himself thrown straight into an adventure. ‘I set off on a train to Waimarama, and ended up working with those Blerta folks – Geoff Murphy, Bruno Lawrence, Alun Bollinger (AlBol) and all them,’ recalls Thomas. ‘This was working on their first real film, Uenuku, a 50-minute Māori language drama. Me and AlBol got stuck up in the hills and had to catch and eat eel’ – quite the experience for a teenager!

After returning to Wellington and leaving school, he was trained as a cameraperson at the National Film Unit (NFU) but considered it too corporate, and decided that the civil service wasn’t for him. ‘I was too wild for the NFU – too self-centred, really. I didn’t want to end up making tourist films.’

Thomas’s independent streak steered him away from pursuing a professional filmmaking career and instead took him to art school. This would set him up for an ongoing oscillation between the worlds of art and filmmaking. He studied at Ilam School of Fine Arts in Christchurch in the late 1970s, alongside film director Vincent Ward. The two worked together on Ward’s A State of Siege.

That title would hint towards some of the unrest in the country in the late 1970s and early 80s. Developing protest movements included the occupation of Takaparawha Bastion Point, Te Matakite o Aotearoa – the Māori Land March, and the work of Ngā Tamatoa and the Polynesian Panthers. Alongside all this were campaigns that were part of an international movement to oppose apartheid in South Africa.

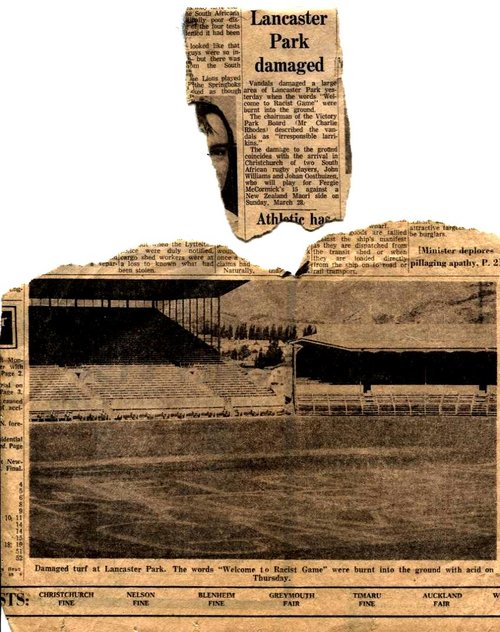

Newspaper clippings showing the Lancaster Park pitch

Thomas had connections with members of HART (Halt All Racist Tours). When a Canterbury rugby player invited two Springboks to play in his 1976 swansong match, Thomas and friends were determined to do something about it. ‘That experience of working with Blerta, their ability to click their fingers and do something, was a total revelation.’ He and a couple of friends bought weedkiller and a sprayer and snuck into Lancaster Park. Thomas had experience as a gravestone engraver, but trying to spray huge letters on a field in the dark was an entirely different challenge. ‘But there it was aimed at the television cameras in 20-foot-high letters: “WELCOME TO RACIST GAME”.’

The action was covered in The Press and on radio. With the success of this action, Thomas and his friends were determined to keep pushing boundaries and standing up for what they believed in.

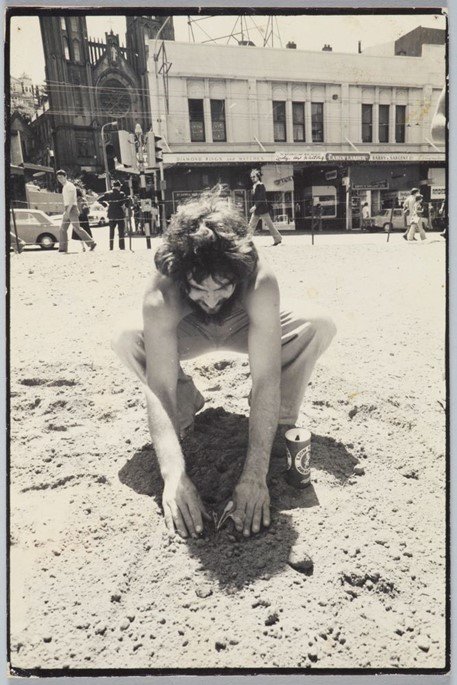

A direct line could be drawn between that pitch invasion and another – ‘the cabbage patch’ planted on a vacant Wellington street corner. In 1976, Thomas was back living in the capital and had been inspired by the land art movement and recent works such as Spiral Jetty (1970). In a unique art installation in 1978, he planted 180 cabbages arranged to spell ‘CABBAGE’. ‘It was art as activism. I was from the Upper Hutt working class and there’s always this approach that you can do it yourself.’ The cabbage patch lasted about six months. It was well-tended and became a hot spot for other creative works. In 2012 the cabbage patch archives (properly Vacant lot of cabbages) were bought by Te Papa for their permanent collection.

Barry Thomas tending to the garden at the cabbage patch

When 1981 and its proposed Springbok Tour rolled around, organisations like HART and the Citizens’ Association for Racial Equality (CARE) were mobilising to stop it. After the agitation of the mid-70s, Thomas was ready to continue his involvement and took his camera skills to the street. ‘We begged and borrowed film equipment, set up camera crews and got filming.’ The violent clashes between anti-Tour protestors and the police that followed are now part of history.

‘It was rough stuff!’ he recalls. ‘It was a fight for egalitarianism. But we were on the right side of history and it was good to capture that for posterity.’ Much of the footage of these protests would eventually become the feature documentary PATU! ‘That film belongs to New Zealand; PATU! is a taonga.’

"That film belongs to New Zealand; PATU! is a taonga."

Throughout the 1980s and 90s, Thomas worked on film and art projects. Through his company Yeti Productions, he got future award-winning animator Stephen Regelous off the dole and they developed computer graphics programmes, including their own visual morphing effects after seeing the video for Michael Jackson’s “Black or White”. Yeti won a number of awards for their commercials.

Thomas and fellow filmmakers like Waka Attewell got themselves in to a niche of ‘community service films’: Attewell made work for groups such as Greenpeace and Thomas worked with Kiwisport – the project to increase schoolchildren’s participation in sport. ‘With the government as the client, you can make some amazing, artistic films.’

A culmination of all this – the different mediums, the rebellious spirit, the work both with and against ‘the system’ – came about with rADz, ‘radical art ads’, which ran in several collections from 1997 to 2001. ‘I always swung between these different worlds. Rather than getting into making features, I went the opposite way and got shorter and shorter. Ads are this short poetic zone and people don’t really want to watch them.’

rADz promotional poster

With this challenge in mind, and having previously worked with the government on films and campaigns, rADz was given $120,000 to make 100 ‘haiku films’. Thomas took these to the newly established TV4 with the following criteria: ‘1. They had to be played with credits. 2. They were played across the board; not just dead time. And 3. They had to pay a nominal $500 per collection of rADz. They paid!’ Thomas says gleefully. ‘Broadcasters do not pay to screen ads. No one had done that before.’

rADz served as a petri dish for wildly creative shorts from a host of emerging filmmakers. Lala Rolls, Greg Page and Nova Paul were among the hundreds of creatives who created or worked on one of the productions. Thomas and Yeti Productions made a further 120 rADz in London, Manchester and Birmingham, and took the collections to several film festivals. A highlight was the Venice Film Festival Critics’ Week selector Fabio Ferzetti who described rADz as ‘searing and brilliant’.

Barry Thomas has a saying: “You work for television, you become a television person”. ‘You make compromises and are constrained in your work, by necessity.’ By setting his own constraints and choosing his projects, Thomas has avoided becoming a television person, or any kind of person he doesn’t want to be.

"You work for television, you become a television person."

What is activism and how does it relate to his work? ‘Activism is putting a stake in the ground and doing what you believe. Dissidents are to democracy what soil is to cabbages.’