By Caitlin Lynch

This year I’ve been working on an Honours dissertation at Victoria University, researching films about the New Zealand Wars, how they have been influenced by changes in the film industry and how understandings of national history have developed. Specifically, I looked at Rewi’s Last Stand /The Last Stand (1940/1949), Utu (1983) and River Queen (2005). While there is a bunch of great literature on the topic and those case studies, there was some information I just couldn’t find through a regular library.

Luckily, Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision were able to help me out with their wide range of sources on New Zealand cinema: full films, restored clips, oral interviews, newspaper clippings, press releases, correspondence and more. After sending a quick email roughly explaining my project, I was able to make an appointment to visit the Jonathan Dennis Library, where staff were able to guide me and provide access to material from the books, press and publicity vertical files and papers from the Documentation and Artefacts Collection.

An important part of my research was understanding how New Zealand Wars films were perceived at the time they were first released. Researching historical film you can become so accustomed to how the film is interpreted, valued and criticised today that you forget audiences from 35 years ago (in the case of Utu) or 78 years ago (Rewi’s Last Stand (1940)) saw these films in a different context, with different historical and cinematic knowledge. Reading newspaper reviews housed in the Jonathan Dennis Library’s vertical files gave me extra insight into how Rewi’s Last Stand and Utu were received by public media in 1940 and 1983.

Hero image: Caitlin Lynch in the Jonathan Dennis Library.

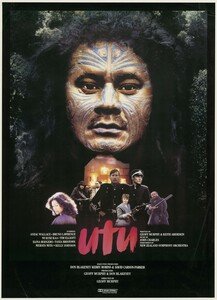

Poster for Geoff Murphy’s Utu (1983) from the Ngā Taonga Documentation and Artefacts Collection.

Reviews of Rewi’s Last Stand confirmed my expectations that the film would be celebrated for its apparent historical accuracy. On the 27th of July 1940, The Dominion’s film review column praised the film for “bring[ing] alive some of the atmosphere of the pioneering days”.[i]

Unexpectedly, despite the fact that Rewi’s Last Stand was first released in Aotearoa New Zealand in 1940 and likely all of its audience would have WWII on their mind, there were only a couple of very minor references made across all of the reviews or promotional material that connected Rewi’s Last Stand and the New Zealand Wars to the contemporary war. Archival material reminds us that connections that might seem obvious with historical hindsight were not necessarily made at the time.

Caitlin Lynch searching in the vertical files.

Ngā Taonga’s newspaper clippings were particularly useful for my research on Utu. While I could have also found newspaper mentions of Rewi’s Last Stand using Papers Past (National Library’s digitised database of New Zealand newspapers) Utu was released outside of the time period Papers Past covers (1839-1950). Ngā Taonga’s collection of Utu reviews saved me hours of trawling through physical copies of old newspapers.

Because Ngā Taonga also collects some international reviews, I was able to find out how Utu (which was recut for the American market without the involvement of director Geoff Murphy) was received in the U.S. Reviewers consistently interpreted Utu’s narrative in relation to race conflicts more familiar to Americans, with The New Yorker calling Te Wheke the “Māori Che Guevara,”[ii] and LA Weekly likening him to an “Apache” warrior. [iii]

Aside from reception information, Ngā Taonga’s archives provided me with lots of behind the scenes facts: the producers of Rewi’s Last Stand’s paid £25 to shoot the battle of Ōrākau at Aotearoa Pā [iv]; Utu’s extras comprised “Black Power groups, Rastafarians, pony, soccer, rugby clubs and schools”.[v] Some of this information made its way into my final research, but more generally it helped me to understand my case studies as processes of production shaped by highly specific contexts and conditions.

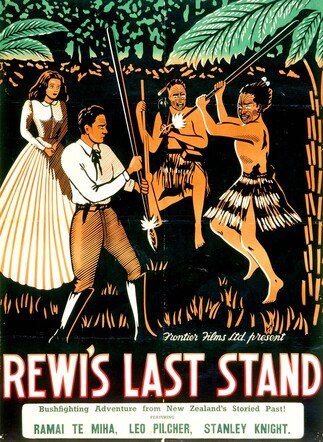

Poster for Rudall Hayward’s Rewi’s Last Stand, 1940. (Ngā Taonga’s Documentation and Artefacts Collection)

Of course, archives always have gaps. There were some questions I could not get a conclusive answer for. When Rewi’s Last Stand was released in Aotearoa New Zealand in 1940 it was 112 minutes long. However, the only version surviving today is a 63 minute recut, titled The Last Stand, made for British audiences in 1949. Like several researchers before me (and likely more to come), I wanted to know what the lost 49 minutes contained, particularly whether there was more to the ending that showed whether Ariana’s injury was fatal or not.

Documentation and Artefacts Collection items, including parts of the original scenario (similar to a script), a novel based on the scenario, letters from the Rudall Hayward (the director) to Alfred Hill (the composer), and oral interviews with Hayward, gave me some clues, but not enough to make any sure claims about Ariana’s fate.

Ultimately, more than answers, what I found in Ngā Taonga’s archives were questions which I would love to follow up on if I had the time. The letters sent from Hayward to Hill when Rudall and the film’s star Ramai Hayward were in London, are a fascinating insight into some of our earliest global filmmakers and the challenges they faced trying to get Rewi’s Last Stand screened in the country that was largely responsible for the conflicts on which the film was based. The range of responses to Utu beg for more inquiry into the complexities of its reception and screening in different communities around the country.

Ngā Taonga’s archives were invaluable to my research. Sometimes the perfect quote fell into my hands, other times my expectations were disproven, and I had to alter my argument. Either way, using the Ngā Taonga archives made my research more accurate, more interesting, and gave me the opportunity to discover information without having to wait for someone else to write about it first!

- [i] Anon. ‘Around the theatres: films showing in Wellington.’ The Dominion. 27 July 1940, page 16. Rewi’s Last Stand Press and Publicity Vertical Files, Jonathan Dennis Library, Ngā Tāonga Sound and Vision, Wellington

- [ii] Kael, Pauline.‘The Current Cinema: Utu.’ The New Yorker. 15, October, 1984, pages 167-174. Utu Press and Publicity Vertical Files, Jonathan Dennis Library, Ngā Tāonga Sound and Vision, Wellington.

- [iii]Anon. ‘Film Pick of the Week.’ LA Weekly. 19-25 October, 1984, page unknown. Utu Press and Publicity Vertical Files, Jonathan Dennis Library, Ngā Taonga Sound and Vision, Wellington.

- [iv] Anon. “Rewi’s Last Stand, Te Awamutu productions: a historical film.” Waikato independent. Circa 1938, page unknown. Rewi’s Last Stand Press and Publicity Vertical Files, Jonathan Dennis Library, Ngā Taonga Sound and Vision, Wellington.

- [v] Parker, John. ‘Utu- A blood and thunder saga of old New Zealand.’ Today. September-October 1982, page 70. Utu Press and Publicity Vertical Files, Jonathan Dennis Library, Ngā Taonga Sound and Vision, Wellington.