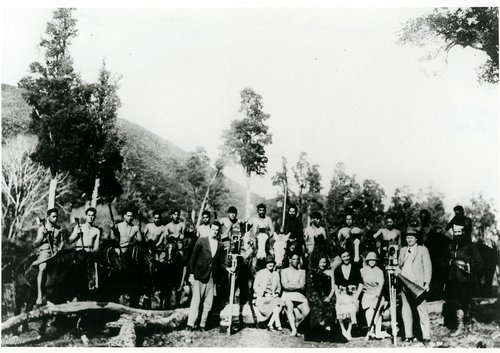

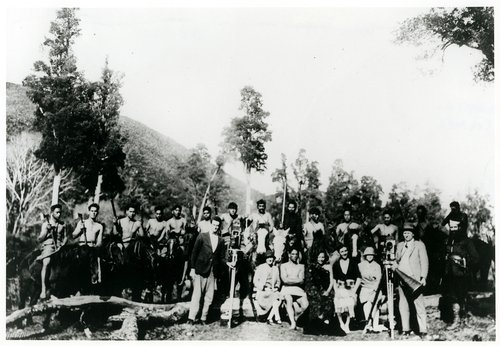

In the photo above. Back: some of the “Māori rough riders”, centre Te Pairi Tuterangi (Te Kooti), Te Tāwhero Tauti / Albert Oliphant Stewart (as Te Kooti’s right hand man). Front: Oswald Caldwell (with camera), Billie Andreasson (Alice Winslow), Tipene Hotere (Baker McLean), Tina Hunt (Monika), Arthur Lord (Eric Mantell), Hilda Maud Hayward, Rudall Hayward (with megaphone) and Tom McDermott (Gilbert Mair).

Occurring over multiple decades of the 19th Century, the New Zealand Wars played an integral role in shaping post-colonial New Zealand. Given their historical significance and enduring impact, some argue that the wars haven’t received their due attention since. With this in mind, it feels worthwhile to examine some of the portrayals of the wars that do exist in the cultural limelight – and consider how these might play a role in shaping our understanding of this period in New Zealand history.

The wars have been explored a number of times on screen, with two prominent examples being Rudall Hayward’s 1927 silent film The Te Kooti Trail, and Geoff Murphy’s 1983 epic Utu. Both films drew on historical events that occurred during the wars but are unique in that they are films of their times – differing stylistically, aesthetically, and in cultural essence.

Annabel Cooper, former Associate Professor in the Department of Sociology, Gender and Social Work at the University of Otago, has a keen interest in the New Zealand Wars and their far-reaching cultural impacts. Cooper authored the book Filming the Colonial Past: The New Zealand Wars on Screen and is co-curator of the exhibition He Riri Awatea: Filming the New Zealand Wars.

We recently caught up with Annabel and asked a few questions about the portrayal of the New Zealand Wars in Utu and The Te Kooti Trail. She kindly provided the following responses.

To what degree do you consider The Te Kooti Trail and Utu to be historically accurate?

The films made very different kinds of claims about their relationship to actual historical events. Hayward’s publicity screamed that The Te Kooti Trail told ‘The Truth!’ and his appeal to audiences was very much based on this idea that they would be witnessing a detailed re-enactment of events. But of course, in making a historical film there are hundreds of decisions that direct our attention and leave out most of what was happening: that’s the nature of writing history as well as making historical films. And Hayward added a romantic plot and a fictional frame, and invented dialogue as historical features always do, because no-one was standing by to record what everybody said at the time.

That said, there are some events — the remarkable example is the scene of Monika’s death — where detailed documentation by an eyewitness did exist, and the film could be staged and scripted with close reference to what was recorded near the time. That scene is so interesting and moving, because it was Monika’s sister Erihapeti, who held her hands as she was executed, who remembered the scene so intensely, and told it to Gilbert Mair, who was her friend, and also Monika’s. Hayward had Mair’s written account and James Cowan’s account drawn from it, but he had also met Mair who very likely told him about it. Hayward used Erihapeti’s words in te reo in the scene. I think it lives very powerfully still, infused with the strong feeling that Mair communicated about it.

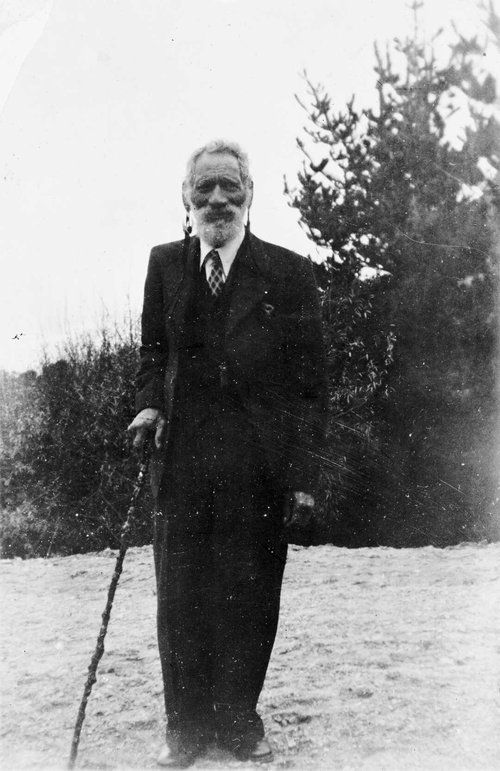

Another example of historical fidelity is in Te Pairi Tūterangi’s performance of Te Kooti, which was rooted in the knowledge Te Pairi had acquired about Te Kooti over many years. In the early scene of Te Kooti preaching, we can be certain that Te Pairi is performing a detailed re-enactment of Te Kooti’s style of preaching and mannerisms, and it was reported at the time that his costuming and haircut made him resemble Te Kooti so closely that people who had known him were startled.

Te Pairi Tuterangi, circa 1930

Photographs owned by Sister Annie Henry (collection). Alexander Turnbull Library, Ref. 1/2-030871-F.

But in Utu — 60 years further away from such immediate personal stories — Murphy and his co-writer Keith Aberdein were taking a broader approach to historical truth. They backed right off the idea of following the career of any specific historical figure. Actually, there is a character called Te Kooti in an early draft of the script but in later drafts, the name is fictionalised, and the character now called Te Wheke is a mix of several historical figures. There are incidents that echo documented historical events but no attempt at re-enactment. Murphy later reflected that ‘the object wasn’t to represent history in any real way, but to create a creative space in which history could be commented on.’ This is very different from what Hayward was doing. Murphy was quite consciously offering a version of past events which spoke to the present of 1983, a time in which our colonial past was being reassessed through vigorous debate and protest action.

The closest Utu comes to a specific incident is the final scene, which is modelled on James Cowan’s story A Bush Court Martial. The story was Murphy’s inspiration for the film (and it was also recorded by Gilbert Mair, who was present, and involved in the event). The way this scene is handled in the film is fascinating. It remains in some ways faithful to the story, which is about how kūpapa troops take control of the fate of a prisoner and are guided by the principle of utu in their decision about who will execute him. But the film makes a much broader statement about violence, and about the tragic dilemmas for Māori dealing with the colonial world — creating the ‘space in which history could be commented on.’ It’s also remarkable in another way. It is the most important scene in the film — everything has been leading up to it — and Murphy effectively handed the scripting and performance of it to actor Wi Kuki Kaa and Māori advisor Te Poroa (Joe) Malcolm. In order to get it right he trusted their expertise in the tikanga and in the history. This is not quite the same as Te Pairi’s responsibility for the performance of Te Kooti in 1927, but it’s a very interesting echo.

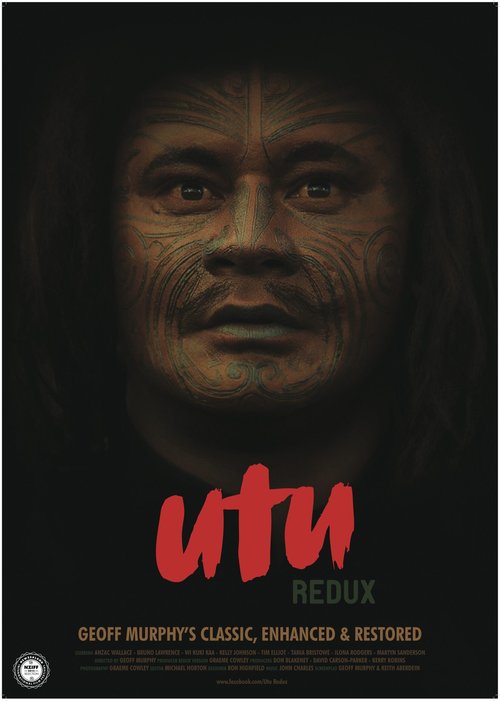

Poster for Utu Redux (2013)

Courtesy of Aotearoa New Zealand Film Heritage Trust and Te Tumu Whakaata Taonga New Zealand Film Commission.

How important was it to Hayward and Murphy to have local community involvement in the production of their films?

It was really important for both of them, but in different ways. Hayward was making his film when there were still people living who had fought in the wars, or were caught up in them. He wanted to involve those people, and he was also keen to try and have descendants and relatives performing the parts of their tūpuna. He went to the historical locations — Whakatāne and Tāneatua — to make the film. He even rebuilt the Te Poronu mill which was the location of the siege in the film, from what remained of its foundations. So the place and the people connected to the events were, to him, very much part of the historical authenticity of the film. There were people who provided information about events. As I’ve already indicated we know that one of them was the Tūhoe rangatira Te Pairi Tūterangi, who had known Te Kooti and who played him in the film. It’s also likely that Albert Stewart, another actor in the film, would have given some historical advice as he had a lot of local historical knowledge (and was related to iwi on both sides of the conflict).

But Utu, which was made 110 years after the events it fictionalises, had a different kind of involvement with local communities. Also, it was made mostly in the general area of the Napier-Taupō road (where the campaign against Te Kooti played out) but not on the site of any specific events. So this was much more a situation of consultation with local marae. Murphy recruited performers locally also — specifically, he needed two groups, the kūpapa commandos and the followers of the resistance leader Te Wheke, and they came from the local farming community and from a Napier rugby club. But aside from that, there were several Māori film professionals who came from the Bay of Plenty and East Coast areas who were critical to the film and I think helped to ensure its integrity within that rohe: especially Merata Mita and Joe Malcolm, who both came from Te Arawa, and Wi Kuki Kaa, who was from Ngāti Porou. These were all figures of considerable knowledge and mana. The documentary Making Utu gives a fascinating insight into how Merata Mita and Joe Malcolm in particular mediated the portrayal of tikanga in the film.

What influence do these films have on creating a collective memory of the New Zealand Wars?

That’s an interesting question. The difficulty with the idea that film informs a collective memory in this case is that the films about the wars, as well as the various documentaries on television and online platforms, have appeared so intermittently, with long gaps between them. So each generation of viewers might be familiar with one, perhaps two productions. The Te Kooti Trail had quite a short viewing life because it was a silent film released just a couple of years before the talkies began to flood into New Zealand. Everyone stopped being interested in silent film of course. In some ways Hayward’s sound version of Rewi’s Last Stand is the film that shaped collective memory the most for its era. That’s because it was almost the only New Zealand-made film that circulated in the mid-twentieth century, and it was widely shown in schools for a long period. So there was a generation, or two, where the kids could all recite ‘ake, ake, ake’ and knew of the heroic stand of the Ōrākau defenders. Utu however continues to have a very faithful following especially among Māori, which has endured through whānau and over generations.

Both films have been described as Westerns. How do these films fit into the definition of a Western in both the 1920s and 1980s contexts?

This question is quite relevant to the link between film and collective memory. We could contrast the limited impact of our few films, with the function that the Western, for example, performed in the US context because they have so many films, and the genre is so well-known for telling a certain type of history. The Western changed its perspective and ethos in response to shifting understandings of colonial history — and this fits with the idea of collective memory, actually, because collective memory alters and is reshaped in response to the present. The fact that we have borrowed and adapted the Western to tell our own stories of colonial conflict is in itself intriguing — filmmakers have had to ask how is our history similar, and in what ways different, to that of US colonial history?

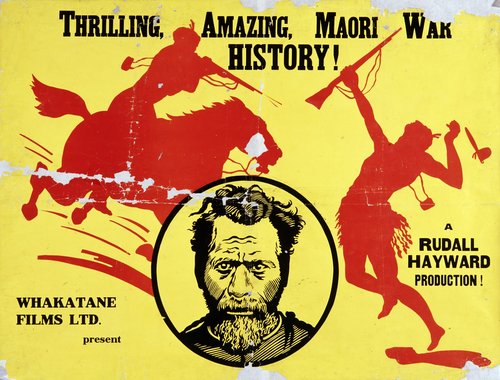

The Te Kooti Trail was made at a time when cinemas were sprouting in all the small towns around the country and they were screening the silent Westerns from the USA — so audiences really knew (and loved) this genre. Including the local people who helped make The Te Kooti Trail — there’s a great horseback chase and you can tell that the young Ngāti Awa men riding those horses knew exactly what kind of movie they were making. They were whooping it up! And Hayward had a very clear idea that this country had historical material that would make films just as good as the ones coming in from the USA. But as the American critic Robert Sklar observed much later, Hayward’s films are more sympathetic to resistant Māori than the US ones of the same period.

Poster for The Te Kooti Trail (1927)

Courtesy of the Hayward Collection. Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision.

Utu belongs to the era of the revisionist Western — when anti-colonial critiques had put the ethos of Western expansion, the great theme of the Western, in a very different light. If Westerns were being made by this time they were likely to be much more sympathetic to the histories of Native Americans. Murphy loved Sergio Leone’s stylised and stylish revisionist Westerns. The look and the sympathies of Utu gesture to this influence. Another echo however is Akira Kurosawa’s Macbeth story, Throne of Blood, set in a misty feudal Japan.

What can a history student learn about the New Zealand Wars from watching these fiction films?

One important lesson that can be drawn from these films, I think, is the fact that historical interpretations aren’t fixed: new knowledge and new perspectives are always altering how we understand the past. We focus on different events and individuals, we interpret actions differently, our sympathies change over time. Historical films are made in the context of their time, and looking back over the different films and their perspectives gives us an insight into how understandings of the past change. I think this sense of ideas and ideologies as always changing is one of the most useful things the study of history does for us — it helps to prevent us getting too fixed in our own views, and to appreciate different, and changing, perspectives even if we don’t agree with them. We see ourselves as being part of history and this long process of change. These films from different eras can help us towards this appreciative openness.

We would like to thank Annabel for providing these insightful and thought-provoking responses to our questions on The Te Kooti Trail and Utu. We’re certainly left with a lot to reflect on — not only about the New Zealand Wars, but about how the interpretation and presentation of such events on screen can both inform and be informed by an ever-changing understanding of our history. It is interesting to ponder how a film made about the New Zealand Wars today might reflect the modern era and our current perspectives towards our history.

The exhibition Annabel has co-curated He Riri Awatea: Filming the New Zealand Wars can be visited at The New Zealand Portrait Gallery Te Pūkenga Whakaata in Wellington, until 6 November. Making Utu, Utu Redux and The Te Kooti Trail are screening at the National Library of New Zealand in October.

The cast and crew members for The Te Kooti Trail (1927) on location

Courtesy of the Hayward Collection. Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision.